|

Posted 1/26/19

A VICTIM OF CIRCUMSTANCE

Building cases with circumstantial evidence calls for exquisite care

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. What can be more suspicious than coming across a parked and unattended pickup truck, finding the body of a strangled woman nearby, then discovering that the vehicle’s owner was the victim’s lover?

That’s the spot in which Horace Roberts found himself. Despite protesting that the woman borrowed his truck, and that he repeatedly called her from a phone booth when she didn’t return, his insistence that they were not having the affair that everyone knew about helped doom him. As did finding the victim’s purse at his home, and what was (incorrectly) thought to be Roberts’ watch at the scene. As did testimony by the victim’s estranged husband, who attended every court proceeding and would later argue against giving Roberts leniency at two parole hearings. Even so, not all the circumstances lined up in the same direction, and it took three trials before a jury returned an unanimous verdict. In 1999 the final set of jurors decided that Roberts was indeed guilty of murder, and a judge sentenced him to fifteen to life.

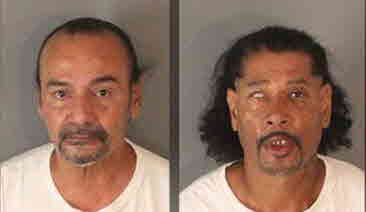

Roberts would still be locked up, too, had it not been for the California Innocence Project. Its dogged pursuit of the case ultimately led authorities to re-examine the victim’s fingernail scrapings, which didn’t yield results the first time. Using new technology that required far less material for a full DNA profile, examiners positively identified the husband’s nephew (right photo) as the source. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen for nineteen years. Meanwhile Roberts sat in prison. He was released and fully exonerated last October. At present uncle (left photo) and nephew await trial for killing the woman and setting Roberts up to take the fall.

Click here for the complete collection of wrongful conviction essays

In “Fewer Can be Better” we mentioned that gathering evidence in victim-type crimes such as murder can be challenging. Ditto here. No one observed the strangling, and all the evidence against Roberts was circumstantial and gathered after the fact. To be sure, there were lots of bits and pieces, and many seemed to fit. That was enough to convince detectives and former prosecutor Brian Sussman, who took the case through each trial, of Roberts’ guilt:

“I thought we were doing the right thing,” Sussman said of the circumstantial-evidence case he presented. “I am sorry from the bottom of my heart. It should have never happened. It’s been a nightmare for him, and I hope he can make something out of the rest of his life. I really do.”

According to the now-retired prosecutor, Roberts turned down a plea deal for voluntary manslaughter and an eleven-year sentence after the second hung jury. So he tried him for a third time. Innocence Project director Justin Brooks thought his persistence reasonable:

[The husband] actually set our client up. It was evidence that was fabricated by, we believe, the actual killer…it’s certainly something can’t be put on the police department or the district attorney’s office in terms of evidence; it was evidence that was actually fabricated.

In contrast with direct evidence, which itself suffices as proof, circumstantial evidence must be applied and interpreted. Here’s the California jury instruction on point:

Facts may be proved by direct or circumstantial evidence or by a combination of both. Direct evidence can prove a fact by itself. For example, if a witness testifies he saw it raining outside before he came into the courthouse, that testimony is direct evidence that it was raining…For example, if a witness testifies that he saw someone come inside wearing a raincoat covered with drops of water, that testimony is circumstantial evidence because it may support a conclusion that it was raining outside. (Cal. 223)

Jurors are instructed that as long as one cannot draw another reasonable conclusion that points to innocence, circumstantial evidence alone is sufficient to convict:

Both direct and circumstantial evidence are acceptable types of evidence to prove or disprove the elements of a charge, including intent and mental state and acts necessary to a conviction, and neither is necessarily more reliable than the other. Neither is entitled to any greater weight than the other…. (Cal. 223)

Also, before you may rely on circumstantial evidence to find the defendant guilty, you must be convinced that the only reasonable conclusion supported by the circumstantial evidence is that the defendant is guilty…However, when considering circumstantial evidence, you must accept only reasonable conclusions and reject any that are unreasonable. (Cal 224)

But what of the motive? Why did Roberts murder his lover? According to the D.A., the reason was simple: “Roberts killed Cheek because she threatened to end their relationship – and he clumsily left his belongings at the crime scene.”

Whether the affair was really on the rocks we’ll never know. But Michael Semanchik, Roberts’ Innocence Project lawyer, found the accused person’s “clumsiness” curious. Why would a killer abandon his vehicle at the crime scene? Why, as reported, would he invite prompt discovery by leaving its lights flashing?

When jurors hung 6-6 at the second trial, prosecutors offered Roberts a reduced sentence in exchange for pleading to voluntary manslaughter. As an innocent man, he turned it down. Semanchik attributed his client’s subsequent conviction to repeated draws from the jury pool; essentially, to chance: “Sometimes it takes that right composition of jurors to sway them and get them across the goal line to convict. And I think that’s what happened in trial [number] three…” Yet the victim’s meandering was no secret; in fact, she and her husband were going through a divorce. Why didn’t the police look into him as well? According to Semanchik, Roberts must have seemed the better target:

There’s always pressure to solve a case from the police and prosecution side and in this case, at the time, back in 1998, although there was a contentious divorce between the husband and wife, there really wasn’t other evidence to support going after [the husband], and so it took this DNA evidence to really turn the tide…

Compelling direct evidence is often absent in murders, so their investigation can require a lot of legwork and laboratory time. Detectives, though, can’t endlessly burn through resources. And pressures to clear homicides can be particularly brutal. Such things can make investigative and prosecutorial decisions in homicide cases especially vulnerable to “confirmation bias”, the tendency to adopt explanations that affirm preconceptions or are particularly expedient. Circumstantial evidence can cut many ways, and ignoring or tailoring things so that everything “fits” is a recipe for disaster. From all indications, that may be a big part of what happened here.

Still, the California Innocence Project mostly blamed the outcome on lies by the husband and nephew. Its lawyers also criticized an antiquated evidentiary standard that supposedly kept a sympathetic judge (he, too, thought the evidence ambiguous) from granting post-conviction relief. Our favorite go-to source in such matters, the National Registry of Exonerations, forged a similar path, selecting “perjury or false accusation” (meaning, by the husband and nephew) from its menu of six causes of wrongful conviction (the others include mistaken witness identification, false confession, false or misleading forensic evidence, official misconduct, and inadequate legal defense.)

To us, the perjury that did happen seems an inadequate container for the “why.” To that extent, the Roberts case is hardly unique. Searching the registry’s approx. 2,300 entries since 1956 using the term “affair” we identified thirteen individuals whose sexual affairs figured prominently in their wrongful conviction. As we perused the entries (see “data source” below) it became apparent that being an unfaithful sexual partner can affect how accused are perceived by witnesses, detectives and other decision-makers. Here, for example, is an extract from a prior post about one of our favorite examples, Scott Hornoff:

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

On August 12, 1989, Warwick, Rhode Island police discovered the body of Vicki Cushman, a single 29-year old woman in her ransacked apartment. She had been choked and her skull was crushed. On a table detectives found an unmailed letter she wrote begging her lover to come back. It was addressed to Scott Hornoff, a married Warwick cop. Hornoff was interviewed. He at first denied the affair, then an hour later admitted it. Detectives believed him and for three years looked elsewhere. Then the Attorney General, worried that Warwick PD was shielding its own, ordered State investigators to take over. They immediately pounced on Hornoff. Their springboard? Nothing was taken; the killing was clearly a case of rage. Only one person in Warwick had a known motive: Hornoff, who didn’t want his wife to find out about the affair. And he had initially lied. Case closed!

What’s more, unlike Horace Roberts, who is black, Hornoff is white. And he was a cop.

Of course, affairs are only a tiny slice of the universe of potentially stigmatizing circumstances. One that’s far more frequently present is a prior conviction, a known influencer of police and prosecutorial decisions. Moreover, felony convictions can be used at trial to attack the credibility of testimony by any witness, including a defendant (for the applicable California law click here; for a discussion click here.) Really, considering all the ways in which investigative lapses and workplace factors can lead to miscarriages of justice, we recommend that the National Registry create a category that takes such factors into account. And that readers who currently practice the policing arts use great care when relying on circumstances to nail their next transgressor.

UPDATES (scroll)

5/8/24 In 1998 two L.A.-area street gangsters, John Klene, 18 and Eduardo Dumbrique, 15, drew life without parole for murdering a rival the previous year. While family members said both were elsewhere when the killing took place, detectives assembled circumstantial tidbits and accounts from self-interested, allegedly manipulated witnesses into a tale that convinced jurors. Years later, an imprisoned gang member confessed to the crime. But his account wasn’t passed on, and it wasn’t until 2021, after innocence project lawyers had stepped in, that Klene and Dumbrique were exonerated and released. They will now divide a $24 million settlement, which L.A. County just approved. Innocence Project

10/23/23 In 1983 a Baltimore middle-school student was gunned down for his Georgetown jacket. Although some witnesses said that 18-year old Michael Willis ran out of the school and tossed a gun, police focused on ex-students Alfred Chestnut, Andrew Stewart, and Ransom Watkins because they were kicked out of the school during an unauthorized visit just before the murder. After harsh questioning, several teens ID’d them from a photo spread, and they were convicted in 1984. More than 30 years later an innocence project stepped in, and the three were exonerated and freed in 2019. Baltimore has agreed to pay them $48 million. As for Michael Willis, he was murdered in 2002. Innocence project

(see 12/4/19 update)

2/25/23 In November 1990 two hunters were murdered in the Michigan woods. Twelve years later a cold-case team used a citizen’s account to pin the killings on Jeff Titus, who disliked hunting on his land and had been seen in the area. There was no physical evidence. Titus denied involvement but was convicted. What the defense never learned was that a serial killer was then on the loose and, once imprisoned, described the killings to a cellmate. A judge threw out the case against Titus, and he was released after serving 21 years. Prosecutors and cops are now on Titus’ side, and a retrial seems most unlikely. Note: Charges were soon dropped and Titus is suing.

10/29/22 No physical evidence linked Maurice Hastings to the 1983 rape/murder in Inglewood, Calif. But after the first jury deadlocked, he was convicted at a retrial. And he would have stayed imprisoned had the Los Angeles Innocence Project not secured an examination of an untested swab from the victim. Its DNA matched that of a convicted (but since deceased) sex offender whose m.o. also precisely matched the circumstances of the crime for which Hastings was charged. A

judge declared Mr. Hastings "factually innocent" in March 2023

6/3/22 Although he ultimately identified Alexander Torres, a key witness

to a 2000 Los Angeles-area murder said that the killer and his victim seemed to be strangers (Torres and the victim were

well acquainted.) Another conceded that he picked Torres from a photo lineup because he most resembled the shooter. And

while Torres was provably elsewhere when the shooting happened, he was nonetheless convicted. But after doing twenty

years, he’s been exonerated. An investigation funded by his family identified the actual shooter, a convicted

robber, and both he and his driver have been arrested.

1/29/20 Twenty-five years after his imprisonment for a gang rape, Rafael

Ruiz was exonerated with DNA evidence. He was first tied to the crime through the victim’s erroneous

identification of the apartment where her assailants lived. She then identified him through a sloppy show-up process even

though his ethnicity didn’t match. His accuser admitted that she had been uncertain but felt “pressured”

by police to make an identification.

12/4/19 Thirty-six years after their imprisonment, Alfred Chestnut, Ransom

Watkins and Andrew Stewart walked out of prison, once again free men. That’s how long it took before the Baltimore

D.A. acknowledged that police and prosecutorial misconduct, including hiding exculpatory evidence and coercing young

witnesses, led to their wrongful conviction in the murder of another teen. Authorities think they know who the real killer

was, but he died years ago. (See 10/23/23 update)

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

When Does Evidence Suffice? Damn the Evidence - Full Speed Ahead! Fewer Can be Better

Guilty Until Proven Innocent Accidentally on Purpose Your Lying Eyes Intrusions Happen

DATA SOURCE

National Registry of Exoneration exonerees (with ID number) whose sexual affair may have helped lead to their wrongful conviction:

David Camm (4291); Jeffrey Hornoff (3306); David Peralta (4275); Carlos Montilla (4986);

Bradley Holbrook (5348); David Lemus (3380); Peter Ambler (4050); Samuel Plotnick (4083); MacArthur Campbell (5043); Madison Hobley (2977); George White (3734); Bruce McLaughlin (4276)

Exonerees where sexual affairs by others may have helped lead to their wrongful conviction:

Clinton Potts (4284); Armand Villasana (3709); John Tomaino (4169); Elicia Hughes (4226)

|