|

Posted 12/11/11

FASTER, CHEAPER, WORSE

Rehabilitation doesn’t lend itself to shortcuts. Neither does research and evaluation.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Is “corrections” a non-sequitur? No, insists NIJ. Its landmark 1997 report, “Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising,” argued that carefully designed and appropriately targeted programs of sufficient dosage and duration can indeed rehabilitate. Intensive, theory based “cognitive and behavioral treatments” were particularly recommended for high-risk populations.

That’s exactly what Project Greenlight offered. Developed by the Vera Institute of Justice and conducted in New York between February 2003 and February 2004, it applied a “cognitive-behavioral” approach to mitigate personality traits associated with offending such as impulsivity, antisocial attitudes and drug use. Inmates would participate in therapeutic sessions, receive housing and employment assistance, and interact with parole agents and social workers before release. Ex-offenders would leave with detailed, step-by-step plans to help them successfully reintegrate into the community.

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

As usual, funding issues butted in. What was intended to be a three-year pilot project was cut back to one year. While that didn’t affect participants, to increase their numbers treatment was slashed to eight weeks from a design length of four to six months. Class sizes were also increased three-fold, from the recommended eight to ten participants to twenty-six. Just like elsewhere in government, notions of “faster, better, cheaper” had clearly taken hold.

Experiments normally include an experimental group and one or more control groups that are virtually identical in all respects but receive no treatment or “intervention.” Because the Department of Corrections intended to house the program in a male-only, minimum-security facility in New York City, Project Greenlight’s experimental group (GL) was comprised of 344 low-risk inmates who originated from (and would be released to) New York City. There were two control groups. One, TSP, included 278 low-risk inmates, also from New York City, who would be housed at the same facility and treated with the department’s five-week Transitional Services Program. A second control group, UPS, included 113 low-risk inmates from outside New York City who would be released from upstate prisons without benefit of a program.

To assure that any differences in outcomes between groups are not due to differences in their composition, experimental subjects are normally picked at random and assigned to groups one at a time. But that’s not what happened with Greenlight. According to the program’s published report correctional officials at first assigned inmates to GL and TSP in large batches, rather than one-by-one. While investigators eventually regained some control, in the end they conceded that the design was only quasi-experimental. However, they declared it was sufficiently robust to eliminate the possibility that the groups were systematically different from the start.

Outcomes were measured one year later. Surprisingly, GL participants seemed substantially worse off. Thirty-one percent of the experimental subjects had been rearrested, compared with 22 percent of TSP participants and 24 percent of those in the untreated UPS group. GL’s also “survived” for substantially briefer periods before arrest.

It’s well accepted that the best predictor of future offending is past offending. That’s consistent with Greenlight data, which indicated that the more serious one’s criminal record the greater the likelihood of arrest after release (coefficients with asterisks denote statistical significance, the more the greater.) But study group also seemed to matter, with Greenlight participants forty-one percent more likely to fail than those treated with TSP. (Similar though statistically non-significant results were reported when comparing GL to Upstate.)

Assuming that the groups were equivalent as to all important characteristics before treatment (we’ll come back to that later), investigators surmised that one or more aspects of Greenlight was making things worse. They speculated about a “mismatch” between the program, which was designed for high-risk offenders, and the low-risk nature of those actually treated. Other likely suspects include GL’s highly abbreviated format, its departure from the original design, poor implementation, and subpar performance by case managers.

Fast-forward to November 2011 when a Project Greenlight update reported outcomes after thirty months. Participants were coded for risk of recidivism, an index comprised of criminal history and other measures. While members of the experimental (GL) group did more poorly overall than those in TSP and UPS, the gap between GL and TSP was statistically insignificant and far outweighed by the gap between both programs and UPS, whose participants fared well while receiving no treatment at all. Low and medium-risk inmates did exceptionally well in UPS, while those at medium and high-risk did especially poorly in GL. Actually, low-risk inmates tended to succeed in each program, with those assigned to GL actually doing considerably better than participants in TSP but falling somewhat short of the untreated Upstate group.

Why did GL succeed with low-risk inmates? Researchers guessed that their personal characteristics (e.g., attention span, cognitive and social skills) were most compatible with the program’s intensity and its compressed format. As for the relative success of the untreated UPS sample, it might reflect the advantage of not unduly upsetting inmates by coercively transferring and programming them shortly before setting them free.

Complex after-the-fact explanations are inherently untrustworthy. What if the presumed effects were artifacts of biased assignment? Indeed, the study’s own data suggests that the groups were different from the start.

Each arrest and conviction variable was at its highest level in Greenlight and at its lowest in the untreated Upstate group, with TSP holding the middle ground. Some of the mean differences appear substantial. So the implications are clear: since the GL group had more hardheads, poor results were inevitable. On the other hand, as the authors pointed out, none of the differences between means reached significance (that’s probably because sample sizes were so small and the fluctuations in scores, measured by standard deviation, so large.) In any event, when nonrandom methods are used to form groups, one cannot assume that participants come from the same population, so statistical significance is meaningless. A more parsimonious interpretation is that the GL group’s bias in the direction of more serious criminal records increased recidivism. Greenlighters seemed least amenable to treatment because they were the most criminally inclined. Upstaters fared relatively well because they were the least. Speculation that Greenlight itself had a criminogenic effect remains just that.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Alas, the conceit that short-term rehabilitative attempts can influence post-release outcomes is nothing new. No matter how carefully designed a program might be, convicts who spend years in prison learning all the wrong lessons are unlikely to be transformed in two months. Still, in an era of shrinking budgets there is a lot of pressure to devise solutions that are better and cheaper than simply locking people up. In “Economical Crime Control,” the lead article in the November/December 2011 ASC newsletter, Philip Cook and Jens Ludwig argue for reprogramming $12 billion a year from prisons to early childhood education and to initiatives that address the “social-cognitive skill deficits” of young persons in trouble with the law.

Effective community-based solutions, though, can be be very expensive. Deinstitutionalization left us with the worst of both worlds: mentally ill persons who are untreated and homeless. To do better with criminal offenders would require far heavier investments in research and evaluation than bean-counters would likely tolerate. “Corrections” may not be a non-sequitur, but “economical” crime control most certainly is.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Murder, Interrupted? Reform and Blowback

Posted 11/20/11

FROM EYEWITNESSES TO GPS

An unusually rich set of criminal cases are on the Supreme Court’s agenda

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Beginning last month, and continuing through April 2012, the Supreme Court is hearing oral arguments on cases accepted for the 2011-12 term. In this posting we’ll look at five where arguments have already taken place, involving eyewitness identification, strip searches, ineffective assistance of counsel and warrantless GPS surveillance.

Witness identification. In Perry v. New Hampshire (Supreme Court, no. 10-8974) the Court will address growing concerns about witness misidentification, a leading cause of wrongful convictions. In this case a physically distant eyewitness to a vehicle burglary identified a man who was being questioned by officers as being the perpetrator. She couldn’t pick him out later from a photographic lineup or at trial. Her original identification was nonetheless admitted and the accused was convicted.

Defense lawyers appealed on due process grounds, arguing that the ID had been tainted since the man was observably in police custody. But the New Hampshire Supreme Court ruled there was no Constitutional violation because police didn’t purposely orchestrate what took place.

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

Perry’s lawyer disagreed. In arguments before the Supreme Court he insisted that eyewitness ID is so prone to error that defendants should be able challenge suggestive identifications before they are admitted as evidence whether police are to blame or not. That didn’t sit well with Justice Kagan, who said that the Court has only excluded eyewitness evidence that was tainted by the authorities. Broadening the net of what is excludable worried Justice Kennedy, who thought it would infringe on the province of the jury, whose job it is to weigh competing explanations. But Perry’s lawyer insisted that normal procedures didn’t suffice for eyewitness testimony because it is unusually resistant to cross-examination.

Our call: Considering their reluctance to create new rules, the Justices are unlikely to let Perry off the hook.

Outcome (1/11/12): Perry’s conviction stands. Perry was picked out from a distance by an eyewitness as he stood detained at the scene of car burglaries. Police, said the Supreme Court, did not try to influence the witness, so Perry’s identification was properly admitted as evidence at trial, where jurors could make up their own minds.

Jail strip searches. In Florence v. Board of Freeholders (Supreme Court, no. 10-945) the Supreme Court will decide if a rule requiring that everyone booked into a jail be strip searched violates the Fourth Amendment.

It’s a nuanced issue. Florence was arrested on a bench warrant for not paying a fine, a trivial matter for which the State conceded he shouldn’t have been jailed in the first place. He was strip-searched twice, once when booked into city jail and again when transferred to the county. Florence claims that such intrusions require reasonable suspicion, and that the minor nature of his offense and lack of evidence that he might harbor contraband made the strip search unreasonable.

Florence sued for deprivation of his civil rights, and a Federal district court allowed his case to proceed. But by a vote of 2-1 the Third Circuit reversed. The prevailing justices were reluctant to dictate how jails should be run. They also fretted that letting jailers decide whom to strip search would open up a Pandora’s box of discrimination claims.

Their reasoning was echoed in the comments made by Supreme Court Justices during oral arguments. While the Justices were troubled by the fact that strip searches seldom uncover contraband, they considered Florence’s proposed “reasonable suspicion” standard impractical. If, as Florence’s lawyer argued, reasonable suspicion was implicit for those arrested for serious crimes, exactly where would one draw the line? Justice Sotomayor, who took on the practical aspects of building reasonable suspicion, noted that key facts about an arrestee’s criminal past might not be known for days. And like the Circuit court, Justice Kennedy was troubled by the discriminatory potential of having jail employees select who would be strip-searched.

Our call: Mandatory strip-search will survive.

Outcome (4/2/12): The Supreme Court upheld the practice of strip-searching everyone who is booked into jail. Justices ruled that strip searches were related to legitimate penal interests, and that trying to make distinctions between potentially dangerous inmates and others was unworkable.

Ineffective assistance of counsel in plea bargaining. There are two cases. Lafler v. Cooper (Supreme Court, no. 10-209) concerns a Michigan man (Cooper) who went to trial on attempted murder, felon with a firearm and other charges because his lawyer advised that repeatedly shooting a woman below the waist would not sustain an attempted murder conviction. In so choosing Cooper turned down a plea deal (he says, reluctantly) that would have resulted in a minimum sentence of four to seven years. As one might expect, he was convicted of everything and got fifteen to thirty.

Cooper hired a new lawyer. His appeal was brushed off by the Michigan courts. But a Federal judge held that the attorney’s abysmally poor advice violated Cooper’s Sixth Amendment rights, and that he should either be offered the original deal or let go. The Sixth Circuit affirmed. Michigan appealed.

In the other case, Missouri v. Frye (Supreme Court, no. 10-444) a repeat drunk driver (Frye) pled guilty and drew a three-year prison term. What he didn’t know was that his lawyer let a plea offer expire that would have reduced the charge to a misdemeanor and the penalty to ninety days in jail. Fry’s conviction was reversed on Sixth Amendment grounds by the state Court of Appeals. Missouri appealed.

In both cases the key issue is straightforward: does the right to counsel attach to the plea-bargaining phase? Lawyers representing Michigan and Missouri argued that it didn’t. That didn’t sit well with the Justices. During oral arguments in Lafler several tried to get Michigan’s lawyer to concede that plea bargaining is a critical phase of the adjudicative process. Recognizing the trap, the lawyer switched his assault to the defendant’s proposed remedy. That was essentially the tack his counterpart took in Frye. In effect, both said there was no remedy.

Our call: Not communicating a plea offer is an incredible blunder. What the remedy may be we’ll soon find out.

Outcome (3/21/12): The Supreme Court decided in Lafler v. Cooper and in Missouri v. Frye that a defense lawyer’s failure to correctly interpret a favorable plea offer (Lafler) or to pass it on altogether (Frye) constitute ineffective assistance when there is a reasonable probability that the offer would have been accepted by the judge. Both cases were reversed.

Warrantless surveillance. In “A Day Late, a Warrant Short” we examined the case of Antoine Jones, a D.C. nightclub owner who is serving a Federal life term for drug trafficking. A key item of evidence was a month’s worth of location data recorded by a GPS device that DEA agents surreptitiously attached to Jones’s vehicle (they had a warrant but it had expired, rendering it invalid.) At times DEA physically tailed Jones, and at other times not. In his appeal to the D.C. Circuit Jones argued that planting the device for such a long duration, without a valid warrant, violated the Fourth Amendment.

The justices agreed, finding that Jones had a reasonable expectation of privacy as to the intimate “mosaic” that was formed by secretly recording a month’s worth of movements. The Government appealed (U.S. v. Jones, Supreme Court, no. 10-1259).

In our post we suggested that the Supreme Court was likely to reverse, as the Circuit’s decision (it upheld the warrantless installation of the device, but not its use) would require judges to speculate about the relative intrusiveness of surveillance techniques. But the Supreme Court threw us a curve. In oral arguments several Justices agreed that GPS devices posed far greater risks to privacy than old-fashioned beepers, which according to precedent can be planted without a warrant. Here’s how Chief Justice Roberts compared the two:

That’s a lot of work to follow the car [with a beeper]. They’ve got to listen to the beeper; when they lose it they have got to call in the helicopter. Here they just sit back in the station and they -- they push a button whenever they want to find out where the car is. They look at data from a month and find out everywhere it's been in the past month. That -- that seems to me dramatically different.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

On the other hand, the Justices seemed unimpressed with the argument by Jones’s lawyer that the mere act of planting a device was an impermissible trespass. And that’s where things rest.

Our call: We’ll gamble and say that the Justices will find a way to require search warrants when using GPS.

Outcome (1/23/12): Attaching a GPS device to a vehicle and using it to track its movements is a “search” under the Fourth Amendment, and therefore requires a warrant.

In the next weeks, as more oral arguments take place, we’ll review Supreme Court cases that address other pressing criminal justice issues. Does the Confrontation clause requires that DNA analysts be made available for cross-examination? Is life without parole a permissible sentence for teens convicted of murder? Do prisoners have a right to replace their State-furnished Habeas counsel? Stay tuned!

UPDATES

3/18/19 Seven years after a New York City jury convicted Otis Boone, a black man, of robbing two white persons, the State’s high court ruled that juries must be informed of the frailties of cross-racial ID. According to jurors at his second trial, held one month ago, that and other weaknesses in the case led to Boone’s acquittal. But prosecutors still insist that Boone was guilty, and an expert who testified at the first trial says it’s not race but witness certainty about ID that really matters.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES AND REPORTS

ACLU report on cellphone tracking

RELATED POSTS

When Seeing Shouldn’t be Believing A Day Late, a Warrant Short Rush to Judgment (Part II)

Your Lying Eyes

Posted 10/16/11

DID GEORGIA EXECUTE AN INNOCENT MAN?

PART III – A QUESTION OF CERTAINTY

Controversial recantations and over-reliance on affidavits helped seal Troy Davis’ fate

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. This much is certain. During the early morning hours of August 19, 1989 Sylvester Coles accosted Larry Young. Coles was soon joined by his gangster buddies Troy Davis and Darrell Collins. One of them hit Young, who ran off. Police officer Mark MacPhail soon arrived. Coles and several witnesses would later testify that Davis struck Young and shot officer MacPhail. Bullet evidence and witnesses also linked Davis with the wounding of a passenger in a vehicle some hours earlier. Both incidents were tried jointly. Davis was convicted of everything, sentenced to death and, ultimately, executed. (For details about the trial see Parts I and II of this series.)

Many notable individuals and organizations including former president Jimmy Carter and the NAACP argued on Davis’ behalf. Amnesty International held vigils on the eve of his execution and declared October 1, the day of his funeral, as a “Day of Remembrance.” Davis’ defenders insisted that he was innocent of everything and that Coles was the one who murdered officer MacPhail. Police were blasted for taking Coles at his word and pressuring witnesses to go along, while prosecutors were criticized for biasing the jury by tying the shootings together with shoddy ballistics evidence and refusing to concede that Davis was innocent even as witnesses began to recant.

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

Facing international pressures, the Supreme Court ordered an extraordinary Habeas hearing. It was conducted in Savannah on June 23 and 24, 2010 by U.S. District Judge William Moore. He delivered his decision two months later. Its first and most important section assessed the evidentiary value of purported recantations by seven witnesses who had testified at Davis’ trial. Four appeared at the Habeas hearing; Davis’ lawyers submitted affidavits for the others.

Witness recantations (pp. 125-50)

Larry Young. He testified at trial that Coles, who was wearing a yellow shirt, was the man with whom he argued, and that a man in a white shirt struck him. Other witnesses described the incident similarly. Young was on the petitioner’s list for the Habeas hearing but he wasn’t called to testify. His new version of events – that he actually saw nothing but that police had told him what to say – came in through an affidavit (pp. 147-49.)

Darrell Collins. He testified at the preliminary hearing that he saw Davis shoot at the vehicle. At trial he said that was a lie. However, he did concede that he saw Davis slap Young. But at the Habeas hearing he recanted everything and claimed that officers had coerced him to implicate Davis (pp. 136-39.)

Jeffrey Sapp. A friend of Davis, he testified at trial that Davis told him he shot the officer but didn’t fire at the car in an earlier incident. He recanted at the hearing, saying that his statement was coerced by police (pp. 133-36.)

Harriet Murray. Larry Young’s girlfriend gave police conflicting identifications of the killer. At the preliminary hearing and trial she settled on Davis as being both the slapper and shooter. She didn’t appear at the Habeas application hearing. Instead Davis’ lawyers presented an unnotarized affidavit in which she attested that the man who argued with Young, which everyone agrees was Coles, was the one who both slapped him and shot the officer (pp. 139-143.)

Dorothy Ferrell. She identified Davis at trial as the shooter. Although she showed up at the Habeas hearing she wasn’t called on to testify. Davis’ lawyers instead presented the Court with her affidavit. In the document she stated that her trial testimony had been was coerced and that she didn’t see who shot officer MacPhail (pp. 143-46).

Antoine Williams. At trial he testified that the man who struck Larry Young was the shooter, and that he was “sixty percent certain” that this individual was Davis. But at the Habeas hearing he said he wasn’t sure who shot the officer, but that police pressured him to identify Davis. Under cross-examination he retracted the part about being pressured (pp. 127-30.)

Kevin McQueen. A jailhouse informer, he testified at trial that Davis confessed. McQueen recanted at the Habeas hearing. He said that he lied to get back at Davis over a fight, or in exchange for consideration on his charges, or both (pp. 130-32.) His was the only recantation that Judge Moore believed.

According to Judge Moore, none of the recantations absolved Davis. Young, Murray and Ferrell’s accounts came in through affidavits, a tactic that he criticized for making cross-examination (thus truth-finding) impossible. Every witness but Murray claimed that their accounts had been coerced by police, a notion that seemed implausible and which officers heatedly denied. Two witnesses who had been in the thick of things, Young and one of his assailants, Collins, now knew nothing. Neither, it seems, did Sapp or Williams. Judge Moore reserved special contempt for Sapp, whom he accused of lying to protect Davis, for example, by claiming to not know of his moniker “RAH”, which stood for “rough as hell.”

Judge Moore had other concerns. He wondered why Murray didn’t simply say she misidentified Davis. (For this and other reasons he dismissed her affidavit as “valueless.”) He had equally little regard for Ferrell’s recantation. Her claim of coercion made little sense as she was the one who first approached officers. And while she was present at the Habeas hearing Davis’ lawyers didn’t call her testify, suggesting that they feared her recantation wouldn’t survive cross-examination.

Other evidence (pp. 150-164)

Firearms. Concerns were raised at the Habeas hearing about questionable forensic evidence that the state presented at trial linking the same gun to both shootings. This issue, which we discussed at length in Part II, was pondered at length by Judge Moore, who ultimately decided that even if the evidence was mistaken it didn’t weigh against Davis’ guilt in the murder because there was abundant testimonial evidence that he killed officer MacPhail (decision p. 164.) Curiously, Judge Moore didn’t address what we thought was the obvious issue, that prosecutors attributed the earlier shooting to Davis so as to bias the jury against him.

Sylvester Coles as the shooter. Several individuals submitted affidavits linking Coles and firearms, which the judge found unsurprising insofar as many on the night of the shooting seemed to be packing a gun. (Coles had already conceded that he was carrying a gun that evening.) But perhaps the most startling new evidence were eyewitness accounts by two persons who said they saw Coles murder the officer, and by several who said that he confessed.

One man, Benjamin Gordon, tried to cover both bases. In 2008 he signed an affidavit in which he said that Coles told him “I shouldn’t ‘a did that shit.” At the Habeas hearing he testified for the first time that he saw Coles pull the trigger. Why didn’t he say so earlier? He was afraid of Coles. Judge Moore found him not credible (p. 158.)

A second witness, Joseph Washington, said through an affidavit that he saw Coles kill the officer. Washington, who testified to that effect at Davis’ trial (he was then in jail for armed robbery) was also thought not credible. According to Judge Moore his trial testimony had been “badly impeached” by evidence that he had been elsewhere when the shooting took place. Judge Moore surmised that Davis’ lawyers didn’t summon Washington to the Habeas hearing to avoid having him impeached once more.

Several witnesses said that Coles incriminated himself. One, Anthony Hargrove, testified that Coles told him that he was the killer. Three others submitted affidavits to the same effect. Judge Moore gave it all little credence, particularly as Coles didn’t testify.

Concluding comments (pp. 164-end)

Judge Moore found Davis’ “new evidence” unpersuasive. Nearly all the recantations were deeply flawed. Other than for the jailhouse informer, whose trial testimony Judge Moore called unbelievable in the first instance, the witnesses were simply not credible. Three “appeared” through affidavits and thus couldn’t be questioned. Coles’ alleged confessions, which came in as hearsay, were equally untestable, as Coles wasn’t there. Judge Moore was clearly peeved at Davis’ lawyers. Instead of asking the Court to have marshals serve Coles, defense attorneys waited until “the eleventh hour” to try (unsuccessfully) to serve him themselves. Judge Moore thought this was an obvious ploy to avoid having him appear at all, as there was nothing Coles was likely to say that would help Davis (decision p. 170.)

Judge Moore’s patience had worn thin:

Ultimately, while Mr. Davis’s new evidence casts some additional, minimal doubt on his conviction, it is largely smoke and mirrors. The vast majority of the evidence at trial remains intact, and the new evidence is largely not credible or lacking in probative value. After careful consideration, the Court finds that Mr. Davis has failed to make a showing of actual innocence that would entitle him to habeas relief in federal court. Accordingly, the Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus is DENIED.

Judge Moore undoubtedly called it as he saw it. Still, it was obvious that given the witnesses’ new slant on things, it would have been impossible to convict Davis had he been granted a new trial. All the pro-Davis publicity had had a devastating effect on the state’s case. Here’s what one of the trial jurors who originally found Davis guilty and voted for death now had to say:

I feel, emphatically, that Mr. Davis cannot be executed under these circumstances. To execute Mr. Davis in light of this evidence and testimony would be an injustice to the victim's family [and] to the jury who sentenced Mr. Davis.

Set Davis aside. It’s the sheer difficulty of retrying cases, let alone those twenty years old, that makes judges such as William Moore jealous about the finality of jury decisions. Yet when the state intends to kill, the moral if not legal calculus is different. To date seventeen death-row prisoners have been exonerated through DNA. It’s also widely accepted (though not by Texas) that one who wasn’t, Cameron Willingham, was wrongfully executed in 2004.

When a judge says “I thought it was a verdict that could go either way,” as one did after a recent conviction, he’s only stating the obvious: that some jury verdicts are close calls. Most citizens would probably agree that in such cases the death penalty is inappropriate. As former New York Governor Mario Cuomo, an opponent of capital punishment recently pointed out, in the real world of criminal justice there is no such thing as absolute certainty. That’s one reason why he favors the alternative of life imprisonment “with no possibility of parole under any circumstances.”

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Would that penalty have satisfied the citizens of Savannah? Probably not. Indeed, many seem more convinced than ever that Davis got what he deserved. For example, check out this editorial in the Savannah News. And when you’re done be sure to peruse this self-serving but nonetheless fascinating commentary by Spencer Lawton, the prosecutor whose efforts may or may not have sent the right man to death.

As for your blogger, he thinks the same as two years ago, that it’s “more likely than not that Davis is guilty.” Of course, “more likely than not” isn’t enough to convict someone of jaywalking.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Did Georgia Execute an Innocent Man? Part I II DOJ: Texas Executed an Innocent Man

Tinkering With the Machinery of Death With Some Mistakes There’s No Going Back

Posted 10/1/11

DID GEORGIA EXECUTE AN INNOCENT MAN?

PART II – JUICING IT UP

Prosecutors wanted a slam-dunk case. They figured out how to get one.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Jurors didn’t convict Troy Davis only for killing a cop. What’s been virtually ignored about this intriguing case is that the jury also found him guilty of aggravated assault in the wounding of a rival gangster a few hours earlier. How these incidents came to be tried together, and most importantly, why, we’ll get to in a moment.

As we mentioned in Part I, Davis and his homies went to a party several hours before officer MacPhail’s murder. Members of a rival gang were also present. While exactly what happened is muddled, a vehicle occupied by the rivals was later fired on. One round struck an occupant, Michael Cooper, in the jaw. Darrell Collins, an acquaintance of Davis, later told police that he, Eric Ellison and Davis had left the party and were on foot when the car drove past and its occupants shouted slurs. Davis pulled a small, black gun and fired. At Davis’ trial Collins recanted, saying that he wasn’t present at the shooting and that officers had pressured him to finger Davis. Ellison also denied being there; however, he did testify that he saw Davis walk back to the party from the direction of gunfire.

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

Cooper, the victim, also took the stand. He said he didn’t know Davis and had no idea who shot him, or why.

Evidence that Davis murdered officer MacPhail seemed far more substantial. Five eyewitnesses, Sylvester Coles, Harriet Murray, Dorothy Ferrell, Antoine Williams and Steven Sanders testified that they were in or near a Burger King parking lot where the incident happened and saw Davis shoot the officer.

Each account had its issues. Coles, the man who originally turned in Davis, was one of three gang members (the other two were Davis and Collins) connected with the incident, so his identification of Davis was an act of self-interest. On the other hand, Murray and Ferrell were ordinary bystanders. However, as we pointed out in Part I, their memories were far from impeccable. When Murray was first questioned by police she couldn’t identify Davis, and she later suggested it was Coles before correcting herself. Ferrell was positive of her identification, but she had seen Davis’ photo on the seat of a patrol car, so her memory was likely contaminated. Williams was only “sixty percent certain” that Davis was the shooter. And while Sanders was sure it was Davis, he had told officers that he wouldn’t be able to identify the shooter.

Two persons testified that Davis told them he killed the officer. One, Jeffrey Sapp, admitted that he and Davis had a falling out; the other, Kevin McQueen, was a jailhouse informer whose account was riddled with inconsistencies.

Considerable circumstantial evidence pointed to Davis. For example, the mugging victim was pistol-whipped, most likely by the same man who later shot the officer. The victim (he ran off before the shooting) and several passers-by who saw the pistol-whipping but not the shooting said the assailant wore a white shirt and dark pants or shorts, attire that matched Davis but not Coles.

Last week we summarized the trial evidence. Now let’s turn to the defense case. As before, our source document is Judge William Moore’s ruling on Davis’ application for a Writ of Habeas Corpus. (For the pertinent section click here and go to page 74. For the full document see “Related Articles and Reports,” below.)

Joseph Washington. A local gangster, then in jail for robbery, Washington testified that he saw Davis at the party but not Coles. Washington said he later went to a location near the Burger King to meet his friend “Wally,” whose last name he couldn’t recall. While there he saw Coles and two other men arguing. Coles hit one of the others. A cop then appeared and Coles fired at him. Washington then returned to the party but didn’t say anything for fear of getting involved.

Tayna Johnson. She saw Davis and Coles at the party. After leaving she heard gunshots coming from the Burger King. She ran into Coles and a man named “Terry.” Coles was nervous and asked her to find out what had happened. She reported back that police were investigating a shooting. On cross-examination Johnson conceded that Coles didn’t act as though he had known. She also said that he was wearing a white shirt.

Jeffery Sams. He saw Davis at the party. He later went with Davis, Collins and Ellison to the pool room. Coles came by and put a shiny gun on the car’s front seat. Sams didn’t want the gun in the car so he placed it outside the pool room. After spending a short time in the pool room he returned to the car. He didn’t see Davis with a gun.

Virginia Davis. Davis’ mother said that her son wore a multicolored shirt to the party. He acted normally when she woke him for breakfast the next morning.

Troy Davis. The defendant testified that he was at the party for twenty or thirty minutes. On leaving he saw a speeding vehicle and heard a gunshot. He went home, changed from his pink and blue polo shirt into another garment (he didn’t specify its color) and accompanied Collins, Ellison and Sams to the pool hall. Coles was already there. Coles later tried to coerce a man into giving up one of his beers. Coles followed the man into the Burger King parking lot, threatened his life and slapped him on the head. The man ran off and Davis left. He then noticed that Collins was running from the area so he did, too. Davis saw a police officer walk into the Burger King parking lot. There was a gunshot, then several more. Coles ran by and didn’t respond when Davis called out.

Davis denied ever speaking with McQueen, the jailhouse informer.

It was a weak defense. Looking back to our first posting and considering the eyewitnesses and such, the prosecution’s case was on balance much stronger. But was it so compelling that a jury should be able to find Davis guilty in two hours? So yes, we’ve left something out. There was physical evidence. A forensic examiner – indeed, the director of the Georgia Crime lab – testified that bullets recovered from Michael Cooper’s head were similar to those taken from officer MacPhail’s body, and that cartridge casings recovered at both scenes were close to identical, thus strongly suggesting that the same weapon was used in both crimes (for the pertinent section of Judge Moore’s opinion click here and go to page 162.) Here is a snippet from the State’s closing argument:

And then there are the silent witnesses in this case. Just as Davis, wearing a white shirt, pistol-whipped Larry and murdered Officer MacPhail, so also did Troy Anthony Davis, using the same gun, shoot Michael Cooper and murder Officer MacPhail.

You will recall the testimony of Roger Parian, director of the Crime Lab, when he was discussing the bullets. He was talking about the bullets from the parking lot of the Burger King and from the body of Officer MacPhail, and he was talking then about comparing that with the bullet from – that was recovered from Michael Cooper’s head when he’d been shot in the face. And what Roger Parian told you is that they were possibly shot from the same weapon. There were enough similarities in the bullets to say that the bullet that was shot in Cloverdale into Michael Cooper was shot – was possibly shot from the same gun that shot into the body of Officer MacPhail in the parking lot of the Burger King.

But he was even more certain about the shell casings. He was quite more certain about that, and he said in fact that the one that was recovered from the Trust Company Bank right across from the Burger King parking lot was fired from the same weapon that fired four other shell casings that were recovered in Cloverdale right down the street from the pool party, Cloverdale and Audubon.

By juicing things up prosecutors fashioned a whole that was considerably greater than the sum of its parts. Supposedly scientific testimony by a highly credible witness linked two frightening events, lending the impression that the accused had been on a murderous rampage and assuring that jurors returned the one verdict that anyone really cared about: murder in the first degree, with aggravating circumstances. That the panel did so in record time only proved the thesis.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Ballistics evidence also piggybacked a weak case on one that was far stronger. Without physical evidence it’s unlikely that the aggravated assault could have been charged. Still, considering the abundant (albeit, imperfect) witness testimony, the murder case would have undoubtedly gone forward and most likely been won.

Of course, a lot can change in two decades. In this series’ third and final post we’ll review what took place at last year’s evidentiary hearing and analyze Judge Moore’s decision to overlook the flaws and let the trial outcome stand.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES AND REPORTS

Evidentiary Hearing Opinion Part I Part II

RELATED POSTS

Did Georgia Execute an Innocent Man? Part I III Tinkering With the Machinery of Death

With Some Mistakes There’s No Going Back Tookie’s Fate is the Wrong Debate

Posted 9/24/11

DID GEORGIA EXECUTE AN INNOCENT MAN?

Deconstructing the murder of a Savannah police officer, with no axe to grind

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. During the early morning hours of August 19, 1989 Savannah police officer Mark MacPhail was in uniform working an off-duty security job at a Burger King when he came to the aid of a citizen who was reportedly being mugged. Officer MacPhail was shot and killed.

Two years ago, in “With Some Mistakes There’s No Going Back,” we concluded that Troy Davis, the man whom Georgia authorities executed three days ago, was more likely than not responsible. Our less-than-ringing endorsement reflected a verdict whose factual basis had been eroded by a string of post-conviction witness recantations, including accusations that the man who fingered Davis later confessed to being the shooter.

Davis’ voluble throng of supporters, led by Amnesty International and the ACLU, never expressed any doubts. ACLU called the execution “unconscionable and unconstitutional,” and not just because they oppose the death penalty, a position with which we happen to agree. Davis, they insist, was at the very least a victim of mistaken identification. He was an innocent man.

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

In our criminal justice system what really counts is what the courts think. And none counts more than the Supreme Court. By 2009 Davis had been turned away by the Georgia Supreme Court and the Eleventh Circuit. His final option was to apply directly to the Supreme Court for a Writ of Habeas Corpus. Normally the justices brush off such applications. But this case was all but “normal.” Facing formidable national and international pressures to insure that justice was done, the high court punted. In what two dissenting justices (predictably, Scalia and Thomas) called an “extraordinary” move, the Court accepted the petition and assigned a trial judge to “receive testimony and make findings of fact as to whether evidence that could not have been obtained at the time of the trial clearly establishes [Troy Davis’] innocence.” Observers said no such step had been taken in fifty years.

Unraveling the merits of the petition fell to United States District Judge William Moore, sitting in Savannah. Prosecutors and Davis’ lawyers presented their evidence on June 23 and 24, 2010. (Click here and here for news accounts.) Two months later the judge filed his opinion. It ran a startling 172 pages. (Click here for Part I, and here for Part II). Davis, the judge ruled, hadn’t come close to meeting his burden. Calling him “not innocent” and slamming much of his evidence as “smoke and mirrors,” Judge Moore effectively sealed the man’s fate. Thirteen months later Davis lay on a table, poison coursing through his veins.

How did the judge reach his damning conclusion? We’ll start by summarizing Judge Moore’s account of the state’s case as told in police reports, the preliminary hearing and trial.

Investigation and Preliminary Hearing

The incident began in a pool hall and spilled over into a Burger King parking lot. There is general agreement that it began with an argument between Sylvester Coles and Larry Young in the pool hall, and that as they moved outside they were joined by two of Coles’ associates, Troy Davis and Darrell Collins. That’s where Davis allegedly struck Larry Young with a gun butt. Young ran off and his yelling drew the attention of officer MacPhail, who came to intervene.

Larry Young told police that he had bought beers for himself and his girlfriend. A man demanded one of the beers, and when he refused the man kept arguing and followed him outside. Young was then accosted by two other men. One struck him on the head with a gun butt. Young ran for help. Several days later police showed him photo arrays. Young couldn’t identify his assailant. But he tentatively identified Davis as the man who demanded the beer. Three weeks later, at Davis’ preliminary hearing, Young said that man was actually Sylvester Coles. Young said that he couldn’t identify the man who struck him, but that he was wearing a white shirt with printing, black pants and a white baseball cap.

Sylvester Coles and his lawyer went to the police one day after the murder. Coles told officers that he was the one who argued with Young, and that Davis struck Young with a small, black gun with a wood handle. Darrell Collins was present but not otherwise involved. Coles said that Davis ran off when a police officer showed up, and that the cop chased him. Coles then heard a gunshot, saw the officer on the ground and fled. Coles admitted that he had been carrying a chrome long-barreled revolver, but said he left it behind while playing pool. Coles gave essentially the same account at Davis’ preliminary hearing.

Darrell Collins told police that on the day preceding the murder he, Davis and a friend Eric Ellison were at a party when rival gang members shouted slurs from a passing car. Davis pulled a small black gun and fired once. That evening they drove to a gas station. On arrival Davis walked to an adjacent pool hall to see Coles. An argument broke out between Coles and another man, and as it moved outside Davis “slapped” the man on the head. Collins was on his way to join them when a police officer appeared, so Collins returned to the car. He heard a gunshot and he and Ellison left. Collins said that Davis was wearing blue or black shorts and a white t-shirt with writing on the front. He didn’t testify at the preliminary hearing.

Many of Davis’ associates were interviewed. Jeffrey Sapp told police that Davis said he slapped a man who argued with Coles and then shot the cop who responded. Monty Holmes told police that Davis said he shot the officer in self-defense when he reached for his gun. Both Sapp and Holmes testified at Davis’ preliminary hearing. Two others spoke with police but didn’t testify at the hearing. Eric Ellison said that he didn’t see the shooting. Craig Young also said he saw nothing. However, he heard that Davis had shot at a vehicle and killed a cop.

There were nine citizen witnesses. Two, Harriet Murray (Young’s girlfriend) and Dorothy Ferrell testified at the preliminary hearing.

Harriet Murray told police that the gunman was wearing a white shirt and dark pants. Ms. Murray could not identify the gunman from the first photo lineup, but picked Davis from another lineup the next day. She also identified Coles as the one who argued with her boyfriend. At the hearing she said that Davis was the man who struck Young and shot officer MacPhail. Davis’ gun misfired the first time, and when the officer reached for his gun Davis fired again, striking the officer’s face, then shot the officer two or three more times as he lay on the ground.

Dorothy Ferrell supposedly told police that she saw officer MacPhail order the gunman from the area hours earlier. She described the shooter as wearing a white t-shirt with writing, dark shorts and a white hat. Ms. Ferrell later said that she had seen Davis’ photo in a patrol car while speaking with an officer on an unrelated matter and told the officer that he was the gunman. She had seen Davis’ photo on TV and was eighty to ninety percent certain he was the one. She repeated this account at the preliminary hearing.

Witnesses Antoine Williams, Anthony Lolas, Matthew Hughes, Eric Riggins, Steven Hawkins, Steven Sanders and Robert Grizzard apparently didn’t testify at the hearing. Antoine Williams told police that the suspect on a wanted poster (Davis) was the one who “slapped” Young and shot the officer. He was apparently shown photographs and said he was “sixty percent sure” that Davis was the gunman.

Trial

Davis was charged with the murder of officer MacPhail and the wounding of Michael Cooper, an occupant of the vehicle that Davis allegedly fired on. Davis pled innocent to everything and was tried in August 1991.

Larry Young admitted his original mixup in identifying Davis. He reiterated that Coles was the man in the yellow shirt who demanded the beer, and that a man in a white shirt struck him on the head.

Sylvester Coles testified essentially as at the hearing. He admitted that he had been carrying a gun, but not when the shooting occurred, and said he didn’t see Davis shoot the officer.

Darrell Collins recanted his testimony about Davis shooting at the vehicle. He said that police pressured him to say so under threat of being charged as an accessory. Collins said that he didn’t see Davis with a gun that day, only in the past. As for the shooting of officer MacPhail, he saw Davis slap the man with whom Coles argued then saw the officer head in their direction. He heard gunshots and ran away. He said that Davis had been wearing a white shirt with writing and blue or black shorts. He also confirmed that Coles put his gun away before entering the pool hall.

Jeffrey Sapp testified that Davis told him he shot the officer but didn’t fire at the car. Sapp admitted that he had lied to police and at the preliminary hearing when he said that Davis went back to finish off the officer so he couldn’t be identified. Sapp said he had made that up to get back at Davis over an ongoing dispute.

Harriet Murray reprised her testimony from the hearing. She reaffirmed her identification of Davis as the shooter. Ms. Murray conceded that when she first picked Davis she said he was one of the three men, not specifically the gunman. She admitted giving inconsistent accounts of the shooter’s physical description.

Dorothy Ferrell testified to essentially the same effect as at the hearing. She identified Davis as the shooter in court. Ms. Ferrell said that she did not see pictures of Davis before spotting his photo in the police car. Contrary to the police report, Ms. Ferrell said that she had only seen officer MacPhail run off someone who looked like Davis. Like Ms. Murray, she conceded giving conflicting descriptions of the shooter.

Three citizen witnesses who apparently didn’t testify at the hearing did so at trial. Antoine Williams said he saw the shooting. He confirmed his “sixty-percent certain” identification of Davis as the man who shot the officer and struck Young, but admitted that he had viewed a wanted poster. Steven Sanders said that he witnessed the shooting. Although he told police that he wouldn’t be able to identify the shooter he nonetheless identified Davis in court. Sanders conceded that he had seen Davis’ photo in the paper. Robert Grizzard testified that he saw the shooting but could not identify the gunman. However, he was sure that it was the same man who struck Young. He described the murder weapon as dark with a short barrel.

Cole’s sister, Valerie Coles Gordon, also testified. She said that she heard gunshots from her home. About fifteen to twenty minutes later her brother came in gasping for breath and changed out of his yellow shirt. He explained that someone was trying to kill him. Davis then arrived, shirtless. Coles gave him his shirt, which Davis donned. But Davis left without it.

Prosecutors called several witnesses to testify about the earlier shooting. Michael Cooper, the victim, said that he rode to a party in a vehicle driven by a friend. His friend got into an argument with rival gang members, Davis among them. When they left their vehicle came under fire and he was struck in the jaw. He didn’t know Davis or the man who fired the gun. Craig Young recanted a prior statement to police, that Davis told him he had argued with “Mike-Mike.” He said officers had pressured him and that he was also trying to get back at Davis over a disagreement. Eric Ellison confirmed that he saw Davis walking back from a direction where shots had just been fired. He said that Davis was wearing a white t-shirt with writing and dark shorts. Ellison testified that he later drove Davis, Collins and another man to the pool hall. He heard gunshots and drove away with Collins and the other passenger, leaving Davis behind.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

And what would a case be without a jailhouse informer? Kevin McQueen, an inmate, said that Davis admitted killing officer MacPhail to avoid being arrested for the earlier shooting. McQueen admitted he had seen a news story about the events and discussed them with other inmates. He denied that his testimony could help him as he had already been sentenced.

In following weeks we’ll summarize Judge Moore’s account of the defense case and review the conclusions that placed Davis on the fast track to execution. It will then be up to readers to decide whether Georgia killed the wrong man.

UPDATES

12/30/19 James Dailey sits on death row for the 1985 stabbing death of a Florida teen. Appeals done, his execution seems imminent. But his alleged accomplice, who’s doing life, says Dailey had nothing to do with it. Lacking physical evidence, authorities relied on the word of a jailhouse informer who swears that Dailey admitted the crime. Jurors convicted Dailey in 1987, and Florida’s governor has said that it’s time for justice to run its course.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES AND REPORTS

Evidentiary Hearing Opinion Part I Part II

RELATED POSTS

Did Georgia Execute an Innocent Man? Part II III Tinkering With the Machinery of Death

With Some Mistakes There’s No Going Back Tookie’s Fate is the Wrong Debate

Posted 5/23/11

THE CHURCH, ABSOLVED

Victims of sexual abuse by Catholic clergy scream “whitewash” over John Jay’s report

Predictably and conveniently, the bishops have funded a report that tells them precisely what they want to hear: it was all unforeseeable, long ago, wasn’t that bad and wasn’t their fault.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Sexual abuse victims have voiced dismay at a suggestion by researchers at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice that the scandal in the Catholic church wasn’t so much its fault as a product of the social upheaval of the 1960s. Reactions in the media have ranged from disbelief to mockery. Here’s what two major newspapers had to say about the so-called “Woodstock defense”:

- New York Times: “...a new study of the abuse problem...cites the sexual and social turmoil of the 1960s as a possible factor in priests’ crimes. This is a rather bizarre stab at sociological rationalization and, in any case, beside the point that church officials went into denial and protected abusers.”

- Los Angeles Times: “A study commissioned by Roman Catholic bishops ties abuse by Roman Catholic priests in the U.S. to the sexual revolution, not celibacy or homosexuality, and says it’s been largely resolved.”

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

To be fair, John Jay’s scholars don’t articulate their conclusions quite so neatly. Yet from the very start the report conveys the unmistakable impression that the Church was also a victim, caught up in forces beyond its control:

- “Social movements, such as the sexual revolution and development of understanding about sexual victimization and harm, necessarily had an influence on those within organizations just as they did on those in the general society” (p. 7)

- “The representation of sexuality was contested in print, film, and photographic media, and increased openness about the depiction of sexuality emerged as sexual acts became more loosely associated with reproduction. These changes were termed ‘sexual liberation,’ and sexual behavior among young people became more open and diverse” (p. 36)

- “The documented rise in cases of abuse in the 1960s and 1970s is similar to the rise in other types of “deviant” behavior in society, and coincides with social change during this time period” (p. 46)

To illustrate the connection John Jay’s authors graphed sexual misconduct complaints received by the Church between 1950-2002. Their data reveals a steady increase during the 1950’s and 60’s, peaking at between 800 and 1,000 per year between 1978 and 1981. The trend then reversed; by the mid-eighties complaints plunged fifty percent. By the mid-nineties less than one-hundred were being filed each year.

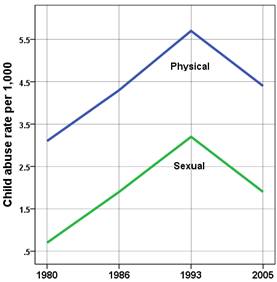

To demonstrate that the decline was part of a larger trend the authors cite data from the National Incidence of Child Abuse and Neglect. This survey measured child abuse in the U.S. in four waves: NIS-1 (1979-80), NIS-2 (1986), NIS-3 (1993) and NIS-4 (2005-06). Applying the rigorous “Harm” standard, which requires “that an act or omission result in demonstrable harm,” the physical abuse of children decreased 15 percent from NIS-3 to NIS-4, while sexual abuse fell 38 percent. (No significant change was evident under the looser “Endangerment” standard.)

However, once we move away from the extreme right tail of the distribution of complaints to the Church, the concordance with national child abuse statistics evaporates. Between 1980 (NIS-1) and 1993 (NIS-3), a period when complaints of abusive priests were already plunging, the national rate of physical abuse of children doubled. Sexual abuse jumped four-fold. (See chart on the right. Rates for NIS-1, 2 and 3 are from the NSPCC; rates for NIS-4 were calculated by the author. All are based on the “Harm” standard.) However, once we move away from the extreme right tail of the distribution of complaints to the Church, the concordance with national child abuse statistics evaporates. Between 1980 (NIS-1) and 1993 (NIS-3), a period when complaints of abusive priests were already plunging, the national rate of physical abuse of children doubled. Sexual abuse jumped four-fold. (See chart on the right. Rates for NIS-1, 2 and 3 are from the NSPCC; rates for NIS-4 were calculated by the author. All are based on the “Harm” standard.)

Child abuse is a secretive crime. Reporting depends on intervention by teachers, caseworkers and police. One explanation for its sharp rise in past years is that society may have started taking better notice of the problem. NIS-3 surmises that better recognition did lead to more reporting. But it was thought unlikely that child abuse rates would have climbed as steeply unless the actual incidence of abuse had also increased. As a contributing factor NIS-3’s authors suggest the catastrophic effect of the drug epidemic of the 1980’s, particularly as drug abuse was frequently cited in the study’s data collection forms.

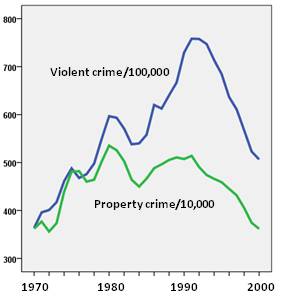

While the NIS report didn’t mention crime rates, they are assumedly linked with problems of social disorganization. Clearly, the trends are similar. Crime increased in tandem with child abuse. And when the well-known “great crime drop” of the 90s got underway, child abuse in the U.S. also plunged.

Could crime and drug use help explain why priests sexually abuse children? First, there is no known theoretical connection. Why would they be more likely to abuse children when crime is on the increase, or less likely when it’s falling? What’s more, the downturn in complaints against priests preceded the great crime drop, like it preceded the drop in the national incidence of child abuse, by a full decade.

If it’s not drugs and crime what about the Woodstock defense? Alas, that seems equally far-fetched. Your blogger, who was a teen in the sixties, doesn’t remember that it was ever OK to sexually experiment on children. Why would priests think otherwise? If there is data to support that odd notion we’d sure like to see it.

On the other hand, pedophiles don’t need to be told that abusing children is OK. Was the Catholic Church admitting large numbers of sexual predators into its ranks ? Was it ignoring signs of abuse? If so, the problem wouldn’t lie with society but with the selection, training and supervision of priests. John Jay’s authors, though, take pains to demonstrate that clergy are no more likely to be afflicted with pedophilia than the general population: “Less than 5 percent of the priests with allegations of abuse exhibited behavior consistent with a diagnosis of pedophilia (a psychiatric disorder that is characterized by recurrent fantasies, urges, and behaviors about prepubescent children)” (p. 3).

John Jay’s report includes a table that depicts the distribution of child victims of priest sexual abuse by age and gender. “Prepubescent,” defined by the authors as age 10 and under, constitutes 18 percent (1,880) of the 10,293 victims in the sample. (The authors also cite a 22 percent figure, but we’ll stick with the numbers in the chart.) Either way, if only about one in five victims are prepubescent, the notion that abusive priests are predominantly pedophiles seems misplaced.

And here’s where we come to a real head-scratcher. What John Jay’s authors don’t reveal is that the controlling description of pedophilia, as set out in the APA’s DSM-IV, a source they repeatedly cite, defines prepubescence differently:

The paraphilic focus of Pedophilia involves sexual activity with a prepubescent child (generally age 13 years or younger). The individual with Pedophilia must be age 16 years or older and at least 5 years older than the child...Those attracted to females usually prefer 8- to 10-year-olds, whereas those attracted to males usually prefer slightly older children.

DSM’s definition of prepubescent as 13-and under would land a majority (probably, most) of John Jay’s abusive priests in the pedophile camp. Naturally, that seriously undermines the Church’s position that it wasn’t aware that pedophilia was a problem. With so many afflicted priests, how could it not know?

The startling age-range discrepancy, which has been noted by the New York Times and other sources, brings the scholarship of John Jay’s report into question. When an academic study is financed nearly exclusively by those with a stake in its outcome (indeed, the Catholic conference holds the report’s copyright), any hints of bias can easily destroy its credibility.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

What steps should John Jay’s authors take? First, they must reexamine their assertion that changing social mores were somehow responsible. It seems far more likely that sexual abuse by Catholic clergy has always been a serious issue, and that reporting went up because of heightened awareness, brought on in part by episodes such as Boston. Really, if the authors are sincerely convinced that pedophilia among priests is rare they ought to prove it fair and square. Instead of massaging (some might say, twisting) data beyond recognition, they might interview former priests. Here’s what one had to say:

Pedophilia is a major problem that is sweeping the church. They’ve been trying to muzzle any information about its happening but it’s causing the priesthood to be destroyed.

If they’re feeling a bit adventurous they might also review examples of abuse by Catholic clergy in Europe, Asia and elsewhere. These are an excellent basis for comparison as they were unlikely to have been influenced by Woodstock. As for the rest of us, a good starting point is the Oscar-nominated documentary “Deliver Us From Evil.” Thanks to its producers’ generosity, all that’s required is to click on the image at the top of this post. But be sure to do it on an empty stomach.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED REPORTS

2011 Philadelphia Grand Jury report Boston Globe on priest sexual abuse 2004 John Jay Report

Posted 5/8/11

PHYSICIAN, HEAL THYSELF

Pharmaceuticals are America’s new scourge. So who’s been writing the prescriptions?

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Did Michael Jackson commit suicide? Improbable as it might seem, that’s essentially the theory being advanced by the legal team representing Dr. Conrad Murray, the physician who awaits trial for allegedly causing the pop star’s untimely demise. Jackson, they suggest, was so distraught about money problems that he guzzled a lethal dose of propofol from the beaker while his doctor wasn’t looking.

A surgical anesthetic, propofol quickly induces sleep and, once consciousness returns, an euphoric state. Its effects are presumably why Michael Jackson repeatedly prevailed on Dr. Murray to inject him with the powerful sedative. The final instance was on June 25, 2009, when the physician, who said that Jackson suffered from chronic insomnia, administered a dose intended to help the entertainer rest up for a busy rehearsal schedule.

Except that this time Jackson didn’t wake up. At Dr. Murray’s preliminary hearing earlier this year a Los Angeles County coroner’s investigator testified that she found a dozen full bottles of propofol in Jackson’s closet, and an empty bottle along with seven vials of prescription sedatives by his bed. Autopsy results confirmed that Jackson’s death was caused by a combination of propofol and other drugs. Prosecutors charge that Dr. Murray had recklessly prescribed and administered them to his patient.

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

Last month the California Medical Board rebuked Dr. Murray, but not in connection with Michael Jackson’s death. He was instead censured for not disclosing on medical license renewal applications that he was behind on child support. Other than being barred from administering heavy sedatives, Dr. Murray’s California, Texas and Nevada medical licenses remain valid. A Los Angeles judge (but not the medical board) did order him to stop practicing medicine in California until the trial is done. It’s now scheduled for this fall.

“This is a completely profit-driven operation that has no medical regard for anyone. These clinics have nothing to do with the welfare of the community.” DEA Special Agent in Charge Mark R. Trouville was referring to the six South Florida “pain management clinics” that the Feds raided in February for allegedly dispensing powerful prescription painkillers to anyone who had the cash.

What the clinics were doing was hardly a secret. Addicts routinely camped out awaiting opening time. Over the course of a year Trouville’s agents paid more than two-hundred visits, going through the motions of being “examined,” getting prescriptions and having them filled. One of the most popular pharmaceutical dispensed at the clinics was oxycodone, the most frequently abused synthetic opiate in the U.S.

When the hammer fell the Feds arrested five doctors and seventeen other employees for illegally prescribing and dispensing controlled substances and covering their tracks with bogus and misinterpreted medical tests. This was the opening strike in “Pill Nation,” an ongoing inquiry into forty-plus Florida “pill mills” that had been dispensing restricted drugs on a cash-only basis, no checks or insurance cards, please. More than sixty doctors are suspected of improprieties. So far fifty-plus have reportedly surrendered their licenses.

Business was generated through word of mouth and the Internet. And the money was good. Agents seized $2.2 million in cash, several homes and dozens of luxury vehicles including Lamborghinis and a Rolls-Royce from Vinnie Colangelo, the owner of the clinics.

With an estimated 850 pain clinics, the Sunshine State attracts prescription drug addicts from much of the U.S. Florida has become such a big draw that clients of a Jacksonville clinic were being transported from Ohio in tour buses. Florida physicians are gaining nationwide notoriety. A Florida doctor will soon go on trial in Kentucky for illegally dispensing pills to as many as 500 residents of that state.

Clinics aren’t the only problem. A week ago Palm Beach officers arrested a physician for furnishing women Oxycodone, Valium and other prescription drugs in exchange for sex. He had once worked at one of the raided clinics and was planning to open his own.

When we think drug abuse, cocaine and heroin normally come to mind. Think again. By 2007 drug overdoses – mostly involving prescription drugs – were killing more people in Ohio than car crashes. In hard-struck Scioto County nearly ten percent of babies born in 2010 tested positive for drugs. Portsmouth, the county seat, has experienced everything from teenagers smuggling painkillers into school to a grisly double murder committed by an addict desperate for his next pill. According to a public health nurse, “around here, everyone has a kid who’s addicted. It doesn’t matter if you’re a police chief, a judge or a Baptist preacher. It’s kind of like a rite of passage.”

Law enforcement is struggling to keep up. State agents recently raided a Portsmouth medical practice suspected of illegally dispensing drugs. Meanwhile a Portsmouth physician is on trial on those charges in Federal court. While the city has enacted a moratorium on new pain clinics, Police Chief Charles Horner says he lacks the resources to wage a meaningful fight. “We’re raising third and fourth generations of prescription drug abusers now. We should all be outraged. It should be a number one priority.”

It’s not just crooked doctors. In the last three years more than 3,000 pharmacies from Maine to California have been hit by robbers seeking painkillers and sedatives for personal use, and with increasing frequency, for resale. Oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin) and alprazolam (Xanax) are the most popular. Frightened pharmacists have responded by turning their businesses into virtual fortresses, elevating counters and installing bulletproof glass. Things got so bad in Maine that the U.S. Attorney agreed to prosecute pharmacy heists under Federal laws that carry especially stiff sentences. Meanwhile a bill in Washington State seeks to raise the minimum incarceration time for robbery when no weapon is shown from three months to three years.

Law enforcement, of course, is just a band-aid. For a more lasting solution one could ask drug manufacturers to reduce their output. Just like gun makers, they crank out far larger quantities of product than could ever be legitimately used. Well, good luck with that. Another tack might be to prevail on doctors to pay more attention to their Hippocratic oaths and less to their colleagues’ Ferraris. Considering the many physicians who churn out medical marijuana prescriptions for a host of ailments real and imagined, good luck with that, too. Think that’s too gloomy a portrait? Here’s how Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez described his “exam”:

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Now I'm not saying it was strange for a doctor to have an office with no medical equipment in it, but I did take note of that fact. And when I described the pain, the doctor waved me off, saying he knew nothing about back problems. “I'm a gynecologist,” he said, and then he wrote me a recommendation making it legal for me to buy medicinal marijuana. The fee for my visit was $150.

Perhaps the key is to attract the right kinds of people into medicine. Recently the medical profession took a (very) tentative step in this direction by recommending that the medical school application process (AMCAS) require that candidates supply information which can be used to evaluate their “integrity and service orientation.”

Sounds good. Until that’s fully implemented, though, keep passing the band-aids.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED WEBSITES, ARTICLES AND REPORTS

CNBC on Rx drug abuse L.A. Times on trial of Conrad Murray CDC - Drug Overdose Deaths Florida

NIDA report on opioid painkillers NIDA Report on Rx drugs and risk of addiction

L.A. Times report on Rx drug deaths GAO report on Medicaid Rx drug abuse

RELATED POSTS

When One Goof is One Too Many Merrily Slippin’ Down the Slope

What’s the Guvernator Been Smoking? What Really Went on at Neverland? They Did Their Jobs

Posted 4/17/11

REFORM AND BLOWBACK

A bad economy spurs more lenient sentencing. And warnings about its consequences.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. As governments reel from sharp declines in revenue they are turning to progressively-minded prescriptions that promise to maintain and even enhance public safety for a lot less dough. Last month we described recommendations by two economists that aggressive law-enforcement practices such as hot-spots policing can scare criminals straight without incurring the expenses of incarceration or, in many cases, the need to make an arrest.

Of course, there are always those who refuse to be deterred. Three reports released this year – one from the National Summit on Justice Reinvestment and Public Safety, the others from the Smart on Crime Coalition and the Pew Center – suggest how we can deal with pesky evildoers in a way that won’t break the bank. Smart on Crime’s remarks pretty well summarize the reformist agenda:

There is no doubt that our enormous prison populations are driven in large measure by our sentencing policies, which favor incarceration over community-based alternatives or rehabilitation. We spend enormous amounts of money keeping people in prison; money that in many cases would be better spent treating addiction or funding community-based programs to reduce recidivism.

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

Indeed, there’s no doubt that sentencing has grown harsher during the past decades. Between 1990 and 2006 the imprisonment rate climbed from 447 to 503 per 100,000. During this period the time actually served behind bars also increased, 29 percent for property crime and 39 percent for violent crime. Meanwhile crime plunged, by about one-third.

Whether more punishment “caused” the crime drop is a matter of endless contention (for our earlier discussions click here and here.) On one side are traditionalists, including prosecutors, police and many economists, who say that imprisonment deserves much of the credit. On the other side are reformers who insist that the relationship between punishment and crime is mostly spurious. Even the few who concede the value of incarceration point out that imprisonment has been cranked up as far as it can go, and that budgetary constraints make current levels impossible to maintain over the long term.

Sustainability looms large in the National Summit report. But it’s not all about saving money:

Despite the dramatic increase in corrections spending over the past two decades, reincarceration rates for people released from prison remain unchanged. By some measures, they have worsened. National data show that about 40 percent of released individuals are re-incarcerated within three years. And in some states, recidivism levels have actually increased during the past decade.

Experts argue that our present system fails badly at preventing recidivism. To get there, and do so affordably, the National Summit recommends several approaches. One, “risk assessment,” seeks to identify the subset of criminals most likely to reoffend, thus making it economically feasible to provide them the supervision, counseling and other services they need. Another, “justice reinvestment,” proposes to shift spending from prisons to communities. A frequently-given example is Texas, which slashed the costs of imprisonment by reducing sentence length. To enhance oversight parole caseloads were also capped, supposedly leading revocations to plunge a steep 29 percent. Perhaps Texas’ way of watching over parolees is a smashing success. Or perhaps the steep decline is due to other, less measurable factors, such as internal pressures to avoid revoking parolees in the first place.

Like other reform organizations, Pew seizes on the lever of economics to press its agenda. On the one hand it concedes that imprisonment might work. (It cites William Spellman, the reluctant punisher who estimated that prison expansion cut violence by 27 percent.) On the other it argues that there are cheaper ways to get to the same place:

Finally, if prisons helped cut crime by at most one-third, then other factors and efforts must account for the remaining two-thirds of the reduction. And because prisons are the most expensive option available, there are more cost-effective policies and programs. For example, it costs an average of $78.95 per day to keep an inmate locked up, more than 20 times the cost of a day on probation.

First, considering just how much crime there is – 1,318,398 violent offenses were reported to the FBI in 2009 – preventing up to one-third of offending (659,199 violent crimes, calculated from a projected 1,977,597) sure seems like a worthy accomplishment. Pew may also be comparing apples and oranges. Prisons are expensive and popular precisely because they offer the ultimate form of deterrence – incapacitation. One cannot compare its cost-effectiveness vis-Ó-vis say, probation without including that certainty in the calculation.

It’s in measures of effectiveness where much of the difficulty in the reformist agenda lies. “Evidence-based” strategies, that new pot of gold at the end of the criminological rainbow, virtually demand that researchers measure the immeasurable. For example, the National Summit report buttresses its conclusions by citing a meta-analysis of adult and juvenile justice programs in the state of Washington. Their cost-effectiveness (programs ran the gamut from prison-based education to post-release family counseling) was calculated by reducing injuries and deaths to dollar amounts. Whether doing so was appropriate was quickly glossed over:

Some victims lose their lives; others suffer direct, out-of-pocket personal or property losses. Psychological consequences also occur to crime victims, including feeling less secure in society. The magnitude of victim costs is very difficult – and in some cases impossible – to quantify. National studies, however, have taken significant steps in estimating crime victim costs...In [one] study [its measures were adopted by this article] the quality of life victim costs were computed from jury awards for pain, suffering, and lost quality of life; for murders, the victim quality of life value was estimated from the amount people spend to reduce risks of death.