|

Posted 11/29/10

FIGHTING THE WALL STREET MOB

Feds use wiretaps and “cooperating witnesses” to expose insider trading

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. While Joe and Jane Citizen nervously watched the value of their 401(k)’s plummet, Raj Rajaratnam was raking it in. According to the Feds, the wealthy founder of the Galleon Group, a hedge fund that invests in technology companies, traded stocks in a way that would warm the cockles of a Mafia don’s heart. Instead of doing his homework and taking his chances, he bribed employees of firms such as Google and Hilton Hotels to give him details about company finances before the information went public.

That’s insider trading, and it’s illegal as heck. Every cent that Rajaratnan made came out of someone else’s pocket. His scheme was wildly profitable. Rajiv Goel, one of Rajaratnam’s many tipsters, allegedly told him that Goel’s employer, Intel, was about to invest in another company. Thanks to the tip, Rajaratnam made a quick $579,000.

For Rajaratnam that was small potatoes. Information that the Hilton chain was about to be sold made him $4 million. Advance knowledge that Google’s quarterly report would show a dip in profits was worth twice as much, a cool $8 million.

Rajaratnam had many sources. Danielle Chiesi, a trader who worked for another hedge fund, passed on tips from her own insiders. “I’m dead if this leaks. I really am and my career is over,” she once said.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

Suspicious trading activity can lead to SEC investigations and civil fines. Indeed, it was a massive SEC inquiry that put the FBI on Rajaratnam’s trail. But convicting someone of a crime is something else again. Convicting someone of insider trading requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt that they purposefully stacked the deck, making admissions such as Chiesi’s crucial. After all, there’s nothing wrong in playing the market like it’s a racetrack, relying on sheer luck and a filly’s (or a stock’s) past performance. So how did the Feds manage to put the bracelets on Rajaratnam and his cohort? By using, for the first time ever, the same tool that’s been so successful against organized crime: the wiretap.

A wiretap is an electronic interception where neither party to a communication has given consent to be monitored. (Wiring up informers or undercover agents is not wiretapping, since they are a “party” to the communication and obviously gave consent.) Feds who want to wiretap must satisfy a District Court judge of several things. There must be probable cause to believe that someone committed an enumerated crime. Wiretapping must also be a last resort, meaning that “normal investigative procedures have been tried and have failed or reasonably appear to be unlikely to succeed if tried or to be too dangerous.”

Rajaratnam and Chiesi are pending trial. They have objected to the wiretaps on several grounds, among them government misconduct. A Federal judge half-agreed but still allowed the intercepts to come in as evidence. We’ll leave arguments about the affidavit for another time. Here we’re interested in how the FBI’s case came together.

Rajaratnam was wiretapped first. Probable cause for his interception came from Roomy Khan, a “cooperating witness” who was one of Rajaratnam’s insiders. This wasn’t her first go-round. In 2001 she had secretly pled guilty to passing Rajaratman information from her then-employer, Intel. Khan agreed to cooperate and her case was sealed. Unfortunately, the FBI’s investigation stalled, probably because the events of 9/11 shifted the agency’s focus to counter-terrorism. Six years later the SEC alerted the FBI that Khan and Rajaratman were at it again. Agents confronted Khan, who folded and agreed to cooperate (she has pled guilty and is angling for a reduced sentence.) Her subsequent phone calls to Rajaratman yielded many golden admissions, for example, that “he knew someone ‘very good’ at Broadcom who could give him ‘the numbers.”

There were three wiretaps on Chiesi. Probable cause was based on information discovered during the Rajaratnam intercepts. Unfortunately, the contents of the tapes are under seal, so what she actually did is unknown.

Fast-forward to November 26 and the arrest of Don Chu. His employer, Primary Global Research, is an “advisory firm” that hooks up traders at hedge funds with persons who are experts about various industries.

Of course, being an “advisor” can provide excellent cover for passing on insider information. A Federal complaint says that’s exactly what happened. Prosecutors accuse Chu of running a stable of “experts” who supply insider information about their employers. It was all going swimmingly until the FBI flipped one of the traders who was buying Chu’s services. His name is Richard Lee.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

For months everything that transpired between Chu and Lee was literally “on the record.” FBI agent B.J. Kang (the same one who brought down Rajaratman) taped Chu providing insider information about two major technology companies, Broadcom and Atheros. Chu was afraid of the SEC, so he looked for company insiders in Asia, “where nobody cares.” One of his best was employed by Broadcom in Taiwan. Listed as a “consultant” on the books of Primary Global Research (and designated “CC-1” in the Federal complaint), the tipster was paid more than $200,000 between 2008-2010.

Now here’s the rest of the story. Richard Lee, the “cooperating witness” who brought down Chu, was one of fourteen traders and employees who pled guilty during the Rajaratnam investigation. Plea agreements invariably require that defendants play ball. Not counting Khan, that leaves a dozen additional “cooperating witnesses.” Did they also wear wires and make recorded phone calls for agent Kang and his colleagues? With word out that as many as fifty hedge funds are under investigation for insider trading, we’ll soon find out.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

You Think You’re Upset? Who’s Guarding the Henhouse? (Part II)

Posted 11/16/10

AN EPIDEMIC OF BUSTED TAIL LIGHTS

LAPD struggles over claims of racial profiling

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Here’s a puzzler for our loyal readers. Click here to read LAPD’s policy on “biased policing”. Then read it again. Now imagine you’re an LAPD officer patrolling an area where shootings involving ethnic gangs have occurred. You spot an older, beat-up car slowly circling the block. It’s occupied by sloppily-attired young male members of that ethnic group. Children and pedestrians are present. Do you: (a) go grab a donut, (b) wait until shots are fired, or (c) pull the car over?

If you answered (c) you may wind up with a lot of explaining to do. Or not. It really depends on which paragraph of section 345 is controlling. The first, which paraphrases Terry v. Ohio, appears to leave race open as one of the factors that can be used when deciding to detain someone for investigation:

Police-initiated stops or detentions, and activities following stops or detentions, shall be unbiased and based on legitimate, articulable facts, consistent with the standards of reasonable suspicion or probable cause as required by federal and state law.”

But the very next paragraph appears to limit the use of race to situations where cops are looking for a specific individual:

Department personnel may not use race...in conducting stops or detentions, except when engaging in the investigation of appropriate suspect-specific activity to identify a particular person or group. Department personnel seeking one or more specific persons who have been identified or described in part by their race...may rely in part on race...only in combination with other appropriate identifying factors...and may not give race...undue weight.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

Section 345’s prohibition against using race as an anticipatory factor has spurred spirited debate within LAPD. While everyone agrees that race should never be the sole factor, many cops don’t think that it should always be out of bounds. In a notable recent conversation (it was, believe it or not, inadvertently taped) an officer told his superior that he couldn’t do his job without racially profiling. Somehow the recording made its way to the Justice Department, which is still monitoring the LAPD in connection with the Rampart scandal. As one might expect, DOJ promptly fired off a letter of warning.

Chief Charlie Beck, who’s struggling to get the Feds off his back, quickly denied that the officer’s comments reflect what most cops really think. Still, the faux-pas reignited a long-simmering dispute between LAPD and the Los Angeles Police Commission, whose president, John Mack, a well-known civil rights activist, has bitterly accused the department of ignoring citizen complaints of racial profiling.

Each quarter the LAPD Inspector General examines disciplinary actions taken against officers during that period. Last year, as part of an agreement that relaxed DOJ oversight, LAPD IG investigators started reviewing the adequacy of inquiries conducted by LAPD into alleged instances of biased policing (LAPD’s preferred term for racial profiling.)

The 2009 second quarter report summarized biased policing complaints for the prior five quarters. Out of 266 citizen complaints of racial profiling, zero were sustained. This was by far the greatest such disparity for any category of misconduct. IG employees examined a random sample of twenty internal investigations of biased policing. Six were found lacking in sufficient detail to make any conclusions. Incidentally, twelve of the police-citizen encounters involved traffic offenses. Ten were for no tail lights, cracked windshields, tinted front windows, no front license plate and jaywalking. An eleventh was for speeding, a twelfth for riding a dirt bike on a sidewalk.

The most recent report, covering the fourth quarter of 2009, revealed 99 citizen allegations of biased policing; again, zero were sustained. The IG reviewed a sample of eleven investigations; it criticized two as inadequate. Four officer-citizen encounters had complete information. Each was precipitated by a traffic violation: one for running a red light, one for no brake lights (the driver later insisted only his supplemental third light was out), one for not wearing a seat belt, and one for tinted front windows.

Earlier this year DOJ criticized the IG’s investigation review process as superficial. Biased policing claims will henceforward be investigated by a special team, using new protocols. Their first product is due out soon.

Cops have so many ostensible reasons for making a stop that divining their underlying motive, if any, is probably a non-starter. That was conceded by no less an authority than the Supreme Court. Here is an extract from its ruling in Whren v. U.S.:

The temporary detention of a motorist upon probable cause to believe that he has violated the traffic laws does not violate the Fourth Amendment's prohibition against unreasonable seizures, even if a reasonable officer would not have stopped the motorist absent some additional law enforcement objective.

It’s widely accepted in law enforcement (and apparently, by the courts) that using all available laws isn’t cheating – it’s simply good police work. That can make it well-nigh impossible to determine whether racial bias was a factor in making a stop. John Mack may not like it, but the commanding officer of Internal Affairs was probably just being candid when he told the police commission that sustaining an allegation of biased policing literally requires that an officer confess to wrongdoing.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

What can be done? Target individuals, not ethnic groups. Selecting low-income, minority areas for intensive policing, even if they’re crime “hot spots,” can damage relationships with precisely those whom the police are trying to help. Aggressive stop-and-frisk campaigns such as NYPD’s can lead impressionable young cops to adopt distorted views of persons of color, and lead persons of color to adopt distorted views of the police. Our nation’s inner cities are already tinderboxes – there really is no reason to keep tossing in matches.

Target individuals, not ethnic groups. Repeat at every roll-call. And be careful out there!

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Driven to Fail Good Guy/Bad Guy/Black Guy (I) (II) Too Much of a Good Thing

Liars Figure Of Hot-Spots and Band Aids Love Your Brother - And Frisk Him, Too!

R.I.P. COMMUNITY POLICING?

Reclaiming professionalism sounds great, but it begs an underlying issue

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Having suffered for years through the mind-numbing rhetoric of community policing, your blogger was thrilled to attend the panel entitled “A New Professionalism” at the June 2010 conference of the National Institute of Justice.

Sparks flew from the very start when Christopher Stone, Guggenheim Professor of the Practice of Criminal Justice at Harvard’s Kennedy School took on – hold your breath – community policing. Placing himself firmly in the ranks of the contrarians, he criticized its “cacophony” of purpose, airing out what many have whispered for years, that by absorbing every promising strategy that comes along, with even the most focused crime-fighting programs labeled as inspired by its principles, the concept has been blurred beyond recognition.

As it turns out Dr. Stone wasn’t there just to slay one dragon. A monograph soon to be released by Harvard’s Executive Session on Policing intends to rehabilitate – hold on to your fedoras – police professionalism. Dr. Stone and his colleagues will argue that their version, snappily entitled “the new professionalism,” does not portend a rebirth of the much-maligned model that dominated American law enforcement in the decades preceding community policing. (To complicate matters some insist that the recent explosion in aggressive strategies such as stop and frisk signals a reincarnation of the “bad” professionalism, but never mind.)

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

There are at least four aspects to the new, improved version (keep in mind that Harvard’s report isn’t out, so this is based on what your blogger scratched out the old-fashioned way):

- A “new accountability” that goes beyond talking about integrity to creating systems that support it; for example, using databases to track officer behavior and warn of emerging problems.

- A “new public legitimacy” that integrates the professional model’s law-centered response with community policing’s emphasis on citizen participation and consent.

- An emphasis on fostering organizations that “transcend parochialism” and can learn, adapt and innovate as circumstances change.

- A “national coherence” that creates common ground among America’s hyper-fragmented police system.

But wait a minute: wasn’t the community concept supposed to be a Swiss Army knife? Didn’t it take care of every important concern? Not according to Dr. Stone. Even its central tenet – that citizens must help shape the police response – has supposedly fallen short. Exactly what “communities” are supposed to do is vague. What’s more, the strategy is silent in areas rife with liberty concerns. How should police deal with political dissent? When should they apply aggressive methods like stop and frisk? How should they employ those new, enticing technologies?

Not so fast, said David Sklansky, Professor of Law and Chair of the Berkeley Center for Criminal Justice. (Full disclosure: David was an Assistant U.S. Attorney while I supervised an ATF squad in Los Angeles. That he didn’t always prosecute when we wished will have no influence on this essay.) While Prof. Sklansky agreed that community policing has definitional issues, one being that communities don’t agree within themselves as to what’s needed, he argued that it nonetheless focuses much-needed attention to the tendency to under-engage with citizens and over-rely on technology. Voicing skepticism about recent innovations such as “information-led” and “predictive” policing, he worried that their preoccupation with numbers harkens back to the same old bureaucratic tendencies that veered professionalism off course. Instead of doing away with community policing he suggested developing an “advanced” version, and we trust that its precepts will be addressed in the forthcoming paper.

Professors Stone and Sklansky were followed by Chief Ronald Davis, East Palo Alto, California. His views reflected the concerns of someone who’s involved in the practical side of things, securing resources and making things happen so that others have something to pontificate about. Although Chief Davis supports improvements, he warned that any departure from the status quo could confuse politicians and grantors. With COPS disbursing millions each year that’s not an idle concern.

Chief Davis also offered a provocative question. Is policing a profession or a vocation? If it’s a profession its rules, practices and techniques should make the national coherence that Dr. Stone finds lacking a non-issue. Yet profound socioeconomic, cultural and political differences between communities, even those located within the same political boundaries, assure that policing will remain far from “coherent” for the foreseeable future.

In his seminal volume, “Varieties of Police Behavior,” James Q. Wilson argued that the centrality of discretion defines police work as a craft. Unlike a true profession, policing doesn’t lend itself to standardized procedures or written directives. It’s mostly learned through apprenticeship, as even the best academies can’t simulate the infinite variety of situations and personalities that officers encounter each day. Policing’s deeply individualized and particularized nature makes its study exceptionally challenging. And we haven’t even touched on how police interact within their own ranks, nor with outsiders.

To understand why cops and chiefs behave as they do we must understand the forces that shape their environment. In past years that was done ethnographically (think Wilson, Manning, Van Maanen and Muir.) Lacking contemporary research of such depth it seems wise to take another look at how the sausage gets made. There are many interesting questions. Crime has supposedly receded, so why have things taken such an aggressive turn? In an earlier post we mentioned the veteran Camden PD captain who was browbeaten during a Compstat meeting because one of his teams made only a single arrest in four days. Whether that one pinch was particularly difficult or noteworthy seemed to be of little interest, which considering the pressures generated by Compstat isn’t particularly surprising.

That’s not to say that constructs such as community policing or police professionalism or the new versions of each have no value. Yet developing a framework that can advance policing to the next level requires far more than from what this (admittedly astigmatic) vantage point looks like a mishmash of ideology, assumptions and superficial observation. So, having discouraged jumping to prescriptions it now seems only fair to make one. Before revising any more paradigms, let’s do the grunt work. If we need a template, “Varieties of Police Behavior” seems an excellent choice. Dr. Wilson sent graduate students to eight communities; with money from COPS we could dispatch them to eighty, and do it regularly. Imagine that: a national survey! Interviewing a cross-section of cops, politicians and citizens couldn’t help but enlighten us about how policing gets done and, most importantly, why.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

First describe; then and only then prescribe. Isn’t that what we insist our students do?

UPDATES

6/26/20 Santa Cruz, Calif., an early adapter of Predictive Policing, has banned it because it biases police attention towards areas populated by persons of color. Its use was suspended by a new police chief in 2017 because doing “purely enforcement” caused inevitable problems with the community. Santa Cruz also banned facial recognition software because of its racially-biased inaccuracies.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES

Quantity and Quality The Craft of Policing

RELATED POSTS

Which Way, C.J.? Too Much of a Good Thing? A Very Dubious Achievement Liars Figure

Slapping Lipstick on the Pig: Part I Part II Part III

Posted 7/4/10

WHAT’S MORE LETHAL THAN A GUN?

Officers have more to fear from accidents than from criminals

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. May and June were terrible months for the California Highway Patrol. On May 7 Officer David Benavides lost his life when his patrol aircraft crashed. One month later, on June 9, motorcycle officer Phillip Ortiz was on a freeway shoulder writing a ticket when he was struck by an errant vehicle; he died from his injuries two weeks later. On June 11 CHP motorcycle officer Tom Coleman was killed when he collided with a truck during a high-speed chase. On June 27 the toll reached five when two officers, Justin McGrory and Brett Oswald were struck and killed by vehicles in separate incidents, McGrory while citing a motorist and Oswald as he waited for an abandoned car to be towed.

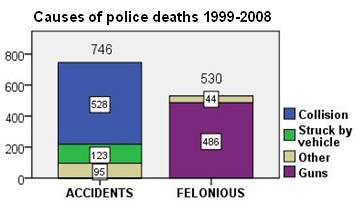

Accidents kill many more cops than gunplay. According to the FBI, 530 officers were feloniously killed in criminal encounters between 1999-2008, with ninety-two percent (486) shot to death. But nearly half again as many (746) perished in accidents. Seventy-one percent (528) died in auto, motorcycle and aircraft wrecks (including pursuits, responding to calls and ordinary patrol, all under “collision”.) Sixteen percent (123) were on foot, ticketing motorists, directing traffic and investigating accidents when they were fatally struck by a vehicle. Thirteen percent (95) were killed in other mishaps, including accidental shootings, falls and drownings.

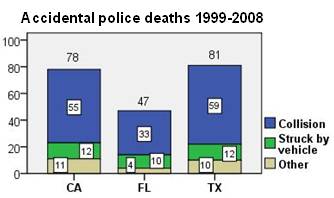

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

Texas led in both accidental and felonious deaths (81 and 52, respectively). California was second in both (78 accidental and 46  felonious). For both the causes of accidental death matched those of the U.S. as a whole. Seventy-three percent (59) of officers accidentally killed in Texas died in collisions, 15 percent (12) when struck by a vehicle, and 12 percent in other ways. California’s proportions were 71 percent, 15 percent and 14 percent. felonious). For both the causes of accidental death matched those of the U.S. as a whole. Seventy-three percent (59) of officers accidentally killed in Texas died in collisions, 15 percent (12) when struck by a vehicle, and 12 percent in other ways. California’s proportions were 71 percent, 15 percent and 14 percent.

Florida was third in accidental deaths (47) and fourth in felonious (22). But its proportion of struck by vehicle deaths was considerably higher, with one officer killed while on foot for every three who died in collisions (in Texas and California it was about one in six.)

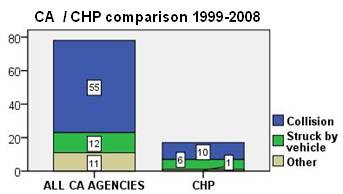

Five dead CHP officers in less than two months is an appalling number, whatever the cause. That three were struck and killed by errant vehicles seems particularly noteworthy. As these two charts demonstrate,

the incidence and distribution of accidental police deaths in the U.S. has been relatively stable over time. But while the numbers are small, California has seen an uptick in deaths of officers struck by vehicles.

According to the FBI 17 CHP officers lost their lives in accidents between 1999-2008.  Ten died in collisions, six when struck by cars, and one in an accidental shooting. Referring to the chart on the right (again, keep in mind the low numbers) it seems that CHP officers are somewhat more likely to be fatally struck by a vehicle than the California norm. Ten died in collisions, six when struck by cars, and one in an accidental shooting. Referring to the chart on the right (again, keep in mind the low numbers) it seems that CHP officers are somewhat more likely to be fatally struck by a vehicle than the California norm.

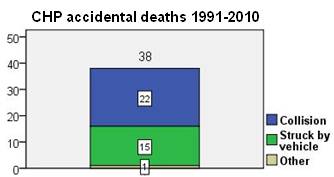

CHP over-representation in the struck-by-vehicle category becomes more evident when we expand the timeline. Online CHP accounts of officer deaths reveal that 38 officers were accidentally killed between 1991 and July 2010. Twenty-two (58 percent) lost their lives in collisions, 15 (39 percent) when struck by vehicles, and one died in an accidental shooting. (Overlapping FBI and CHP data were reconciled except for one case in 2000 and one in 2003.)

Considering where CHP officers spend their time that’s hardly surprising. Making stops on freeways and interstate highways exposes them to high-speed traffic, where there is little opportunity to correct one’s mistakes or accommodate errors made by others. All bets are off when drivers are tired, distracted, intoxicated or driving faster than conditions warrant.

Police are well aware of the dangers. In 2003 the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) and NHTSA formed a committee, LESSS, to study ways to mitigate the hazards of traffic stops. Its initial recommendations suggested enhancing police car resistance to rear-end crashes, packing trunks to avoid the penetration of fuel tanks and passenger compartments in rear-end collisions, improving the visibility of officers and vehicles, widening traffic lanes and building shoulders, enacting “move over” laws to slow oncoming traffic and keep it away from stopped police cars, and devising best practices for safely positioning officers and vehicles. An appendix listed traffic stop procedures in use by a dozen law enforcement agencies, including the CHP. In a related article the IACP’s Police Chief magazine, while conceding there were differences in opinion, recommended, among other things, that officers “minimize their...time in cruisers and prepare citations and other documents outside their vehicles whenever feasible.”

In 2005 LESSS issued a roll-call video, “Your Vest Won’t Stop This Bullet”. Reproduced in print by Police Chief, it offered tips to enhance the safety of traffic stops. Suggesting that insofar as possible officers stay out of their cars until ready to leave, it suggested that if they had to use a radio or such they strap in to avoid becoming a projectile should the vehicle be struck.

Why abandon a metal container to take one’s chances on foot? Thanks to the Arizona DPS, which documented the risk in 2002, word spread that Ford Crown Victoria Police Interceptors were susceptible to catching fire in high speed rear-end collisions. Taken on (some say, reluctantly) by NHTSA, the vulnerability led to a number of recommendations, including the suggestion that officers carefully pack their vehicle’s trunk. LESSS didn’t come out and say so, but the risk of these fires (about a dozen cops had already perished in them) undoubtedly influenced their recommendation that officers on traffic stops keep out of their cars.

Traffic stops aren’t the only hazard. Eight of the fifteen CHP officers struck and killed by cars between 1991-2010 weren’t ticketing anyone: two were investigating unoccupied cars, three were at an accident site, and two were directing traffic. Standing on a roadway is risky, and particularly so when motorists are impaired (intoxicated drivers were involved in at least a third of the officer deaths.) Being under the influence, though, doesn’t fully explain why someone would veer into a traffic stop. One possible explanation well known to driving instructors is target fixation, the tendency to steer in the direction where one is looking rather than where they intend to go. Suppose for example that emergency lights catch the attention of a drunk, sleepy or unskilled driver. Depending on the circumstances, their impairment might keep them from correcting in time to avoid running into the scene. To that extent bright warning lights could actually be counterproductive.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Clearly there’s a long way to go to make cops safe. One hopes that the CHP’s recent tragedies spur renewed efforts to counter the plague of accidental deaths that beset law enforcement. It’s the least we can do for our police.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

Posted 5/16/10

TOO MUCH OF A GOOD THING?

NYPD’s expansive use of stop-and-frisk may threaten the tactic’s long-term viability

“These are not unconstitutional. We are saving lives, and we are preventing crime.”

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. That’s how department spokesperson Paul J. Browne justified the more than one-half million “Terry” stops done by NYPD officers in 2009. But not everyone’s on board. A current Federal lawsuit by the Center for Constitutional Rights charges that the department’s own statistics (NYPD must keep stop-and-frisk data in settlement of an earlier case) prove that its officers routinely and impermissibly profile persons by race.

In Terry v. Ohio (1968) the Supreme Court held that officers can temporarily detain persons for investigation when there is “reasonable suspicion” that they committed a crime or were about to do so. Persons who appear to be armed may also be patted down (hence, “stop-and-frisk.”) Later decisions have given police great leeway in making investigative stops. For example, in U.S. v, Arvizu (2002) the Court ruled that officers can apply their experience and training to make inferences and deductions. Decisions can be based on the totality of the circumstances, not just on individual factors that might point to an innocent explanation.

Last year NYPD stop-and-frisks led to 34,000 arrests, the seizure of 762 guns and the confiscation of more than 3,000 other weapons. Eighty-seven percent of those detained were black or Hispanic. Since they only comprise fifty-one percent of the city’s population, to many it smacked of racial profiling. In its defense, NYPD pointed out that fully eighty-four percent of those arrested for misdemeanor assault in 2009 were also black or Hispanic. Its stops, the department insists, are proportionate to the distribution of crime by race.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

There is data to support both views. A 2007 Rand study found only a slight disparity in the intrusiveness and frequency of NYPD stops once differences in crime rates are taken into account. But a 1999 analysis by the New York Attorney General concluded that the disparity in the frequency of stops could not be explained by racial differences in criminal propensity.

Dueling studies aside, NYPD concedes that blacks, Hispanics and whites who are stopped are equally likely to be arrested (for all races, that’s about six percent.) Indeed, blacks are less likely than whites to have weapons (1.1 versus 1.6 percent.) So why are blacks and Hispanics far more likely to be stopped in the first place? According to NYPD, that’s because anti-crime sweeps usually take place in high-crime (read: poor) precincts where many minorities happen to live.

It’s a truism that policing resembles making sausage. Even when cops try to be respectful, no amount of explanation can take away the humiliation of being stopped and frisked. Although NYPD executives and City Hall argue that the tactic has been instrumental in bringing violent crime to near-record lows, a recent New York Times editorial and a column written by Bob Herbert, one of the city’s most influential black voices, warn that its use has driven a wedge between cops and minorities.

NYPD’s aggressive posture harkens back to the grim decade of the 1960’s, when heavy-handed policing lit the fuse that sparked deadly riots across the U.S. Encouraged to devise a kinder and gentler model of policing, criminologists and law enforcement executives came up with a new paradigm that brought citizens into the process of deciding what police ought to be doing, and how. The brave new era of community policing was born.

It wasn’t long, though, before observers complained that the newfangled approach was of little help in reducing crime and violence. Spurred for more tangible solutions, academics and practitioners devised problem-oriented policing, a strategy that seeks to identify “problems,” which may include but are not limited to crime, and fashion responses, which may include but are not limited to the police. But despite its attempts at practicality, POP’s rhetorical load is substantial, while its strategic approach is not much different than what savvy police managers have been doing all along.

Then CompStat arrived. To be sure, police have always used pin maps and such to deploy officers. CompStat elevated the technology. More importantly, it prescribed a human (but, some argue, not necessarily humane) process for devising strategic responses to crime and holding commanders accountable for results. It was introduced, incidentally, by the NYPD.

Compstat has been criticized for placing unseemly pressures on the police. Its preoccupation with place, though, resonated with criminologists who had long believed that geography was critical. Soon there was a new kid on the block: hot-spot policing. An updated, more sophisticated version of a strategy known as selective enforcement, it encourages police to fashion responses that take into account the factors that bind geography to crime. It’s not just that a certain kind of crime happens at a certain time and place, but why.

After forty years of ideological struggle and experimentation vigorous policing has come back in style. For an example look no further than the campaign pledge by Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter to attack the city’s violence epidemic with hot spot policing and “stop, question and frisk” His call to action has been echoed in cities across the U.S. From Newark, to Philadelphia, to Detroit, Omaha and San Francisco, police are using a variety of aggressive strategies including stop-and-frisk to restore the peace and get guns off the street.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

That’s the good news. The bad news is that from Newark, to Philadelphia, to Detroit, Omaha and San Francisco.... Benefits don’t come without costs. Stop-and-frisk is no doubt effective, yet as recent events in New York City demonstrate it’s not without potentially serious consequences. An inherently elastic notion whose limits officers frequently test, Terry is more than ripe for abuse. Of course, whether NYPD’s enthusiastic embrace has stretched stop-and-frisk beyond what the Supremes intended will be the subject of litigation for a long time to come. Let’s hope that events on the ground don’t make the decision moot.

UPDATES (scroll)

5/6/24 A meta-analysis of 56 studies concludes that crime can be significantly reduced in beset areas by addressing problems of physical disorder (e.g., trash, graffiti) and of “social incivilities” including public urination, prostitution, panhandling, open drug dealing, loitering and drunkenness. While police can help, their benefit comes not from their application of “aggressive order-maintenance strategies” but rather through their participation in joint efforts with service providers and community groups.

4/4/24 Philadelphia’s struggles with crime led Cherelle Parker, its new Mayor, to declare “a public safety emergency” in January. Among other things, she supports “stop and frisk,” a practice that her police force reportedly abused in past years. Shootings involving ski-masked gunmen also recently led the city to ban wearing ski masks and balaclavas in public places. That, too, has brought on a great deal of criticism from civil libertarians. But it’s not simply a matter of race. Mayor Parker and Anthony Phillips, the councilmember who spearheaded the ski mask ban, are both Black.

2/7/23 During the post-Floyd era many specialized police anti-crime teams were disbanded. But violence has led many to return, albeit in “revamped” fashions that supposedly avoid the pitfalls that shut down their predecessors. Denver, New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Portland, Aurora and other cities are experimenting with teams whose rules now emphasize that “the rule of law matters” and that officers must not “stop and frisk everything that moves.” Memphis was also on the list, but then came “Scorpion” and Tyre Nichols.

3/28/22 “...a return to ‘broken-windows’ policing makes me feel like it’s 1994 and Rudy Giuliani is the mayor, stop-and-frisk is out of control, and the N.Y.P.D. is harassing Black and brown New Yorkers.” No matter that the new mayor, former NYPD captain Eric Adams, is Black, his moves to reinstate an anti-gun unit and aggressively address disorder lead a Brooklyn politician to fear that NYPD is set to replay its troubled, Compstat-driven past. But the Mayor insists that police misconduct will not be tolerated.

11/18/19 “The way it was used is racist.” Presidential contender Michael Bloomberg announced profound regrets for promoting NYPD’s stop-and-frisk campaign while he was the city’s mayor. Bloomberg says only a sliver of those stopped had guns and that the practice - which he claims to have wound down - led to estrangement from the Black and Latino communities.

10/20/18 New York City’s new “Right-to-Know Act” requires, among other things, that officers who lack “reasonable suspicion” (as legally defined) to frisk or search hand out business cards, ask for consent, and inform persons that they may refuse. Should a dispute later arise, available body cam footage must also be provided.

8/24/18 In June 2017 NYPD paid out $75 million to settle a lawsuit that charged a quota system led officers to issue more than one million legally insufficient summonses between 2007-2015. That settlement has led NYPD to formally train officers about its “no quota” policy. NYPD’s commissioner recently threatened to discipline supervisors who put quantity over quality. But problems apparently persist. Twelve minority officers - the “NYPD 12” - have an active lawsuit charging that they were punished for not meeting arrest expectations. Their action is the subject of a new, award-winning documentary: “Crime + Punishment.”

10/21/17 A Court monitor asked the judge overseeing the below settlement to order that NYPD change its evaluation process so that officers are primarily judged on the quality of their street stops instead of their number.

6/30/17 According to the Federal monitor overseeing the settlement street stops in NYC plunged from 191,851 in 2013 to 22,563 in 2015. The racial gap among those stopped has also narrowed.

2/4/17 A court settlement now bars NYPD from stopping, frisking and arresting alleged trespassers “hanging around” private apartment buildings, without reasonable suspicion they were committing a crime. Prior settlements covered the same activities at city subsidized housing.

1/24/17 New York settled a Federal lawsuit for issuing “hundreds of thousands” of groundless summonses during its discontinued stop-and-frisk campaign. Its bill? Up to $75 million.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

“Numbers” Rule - Everywhere Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job (I) (II) Turning Cops Into Liars

A Conflicted Mission Place Matters Scapegoat (I) A Workplace Without Pity Two Sides

Mission Impossible Driven to Fail A Not-So-Magnificent Obsession Police Slowdowns II

Why do Cops Lie? Be Careful (I) (II) Ideology Trumps Reason

Good Guy/Bad Guy/Black Guy (I) (II) Three Perfect Storms The Numbers Game

Turn Off the Spigot N.Y.P.D. Blue Forty Years After Kansas City Which Way, C.J.?

Slapping Lipstick: I II III What Can Cops Really Do? Liars Figure Of Hot-Spots and Band-Aids

Love Your Brother...and Frisk Him, Too!

RELATED ARTICLES AND WEBSITES

New York Magazine Series on NYPD problems Official NYPD Monitor website

Posted 1/17/10

SEE NO EVIL, SPEAK NO EVIL

Why don’t witnesses come forward? Often, for a very good reason

“These rats deserve to die, right or wrong? . . . My war is with the rats. I'm a hunt every last one bitch that I can, and kill 'em.”

Extract from wiretap of Philadelphia drug lord Kaboni Savage, charged in 2009 with ordering seven murders.

“If you see something, you better look the other way...Don't tell nothing unless you can take care of yourself, because the city don't have nothing in place to help you.”

Philadelphia resident Barbara Clowden commenting on the murder of her sixteen-year old son only days before he was to testify against the man who tried to burn down their home.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer thirteen witnesses or relatives of witnesses have been murdered in the city of brotherly love since 2001. Philadelphia does have a witness assistance program, currently funded at about $1 million per year. But despite the danger – Ms. Clowden’s son, Eric Hayes, was gunned down far from their old neighborhood – help is limited to paying for a motel room and living expenses, and that only for four months. Beneficiaries must sign a 13-page form that requires them to stay away from their former neighborhoods and avoid those they left behind. That’s not unusual. Because relocated witnesses tend to return to their old haunts, no less an authority than the U.S. Department of Justice recommended that cities with witness protection programs draft detailed contracts to forestall liability.

Witness intimidation is a major national concern. According to a 2006 study it figured in nearly a third of Minneapolis murders and half of its violent crime. It’s supposedly why Trenton’s citizens are reluctant to help police, and why Boston’s cops cleared less that four in ten homicides. None of this should prove surprising. Nearly two decades ago about one-third of Bronx County (NY) criminal court witnesses reported they had been threatened; of the remaining two-thirds, a majority said they feared reprisal.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

What can be done to discourage intimidation? The Justice Department has recommended several strategies, including admonishing defendants to stay away from witnesses, keeping dangerous persons in jail until trial, strengthening penalties for making threats, and vigorously prosecuting those who do. Of course, none of these approaches is fail-safe. In-custody defendants can get friends to do their bidding. Prosecuting intimidators after the fact doesn’t solve the original problem. Doing so also requires – you guessed it – a willing witness.

Spending more money protecting witnesses would help. Still, with 14,180 murders and 1,382,012 violent crimes in 2008, relocating everyone is impossible. What’s more, few persons are eager to upend their lives for the sake of putting someone in jail. Those who do are prone to break the rules, occasionally with lethal consequences. Consider the case of 23-year old Chante Wright. Placed under protection of US Marshals after witnessing a homicide in Philadelphia, she was shot and killed only hours after returning home to visit her ailing mother.

If getting witnesses to cooperate is difficult, what about compelling them to testify under penalty of law? DOJ discourages the practice, warning that it can “backfire” and lead those who might eventually cooperate to “forget.” On the other hand, your blogger knows from experience that once such witnesses take the stand they usually tell the truth. Those who prevaricate can be impeached, and particularly if they’ve made inconsistent verbal or written statements in the past. Indeed, misbehaving witnesses have often influenced jurors to convict.

That, in fact, has been the experience in Philadelphia. A defense lawyer and former D.A. praised its prosecutors, saying that they’re “among the best in the country in trying recantation cases. They've raised it to an art form.” Detectives try to “lock in” witnesses by getting detailed statements early on. And should witnesses clam up or change their minds, officers are more than happy to take the stand and read what they were told, “line by line.” Prosecutors have even ordered the arrest of material witnesses to guarantee their availability come trial. To prevent intimidation court records must be signed out with photo ID, and D.A.’s often ask that defense lawyers be prohibited from giving clients copies of police reports (reproducing and distributing official documents on the street is a common intimidation technique.) Over a defense objection, a scared female witness was even allowed to take the stand while draped in a burka.

Whether one asks or compels witnesses to testify, it’s impossible to avoid the underlying moral dilemma. How can we balance their safety against the imperatives of fighting crime? In July 2005 two assailants shot and killed Philadelphia resident Lamar Canada over a gambling debt. An eyewitness, Johnta Gravitt, voluntarily identified one of the shooters as Dominick Peoples. Gravitt’s statement was supported by Martin Thomas. A friend of Peoples, he told police that the suspect buried the guns used in the shooting in his backyard (they were dug up.) It was an open-and-shut case, at least until ten days after the 2006 preliminary hearing, when Gravitt was gunned down. Someone then posted a copy of Thomas’ statement on a local restaurant wall. It bore the ominous inscription, “Don't stand next to this man. You might get shot.” Thomas stopped cooperating. Forced to appear at Peoples’ trial two years later, he recanted everything.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Peoples was convicted of killing Canada. Gravitt’s murder remains unsolved. As of this writing, Thomas hasn’t been harmed.

UPDATES (scroll)

7/7/25 According to an inquiry by the New York Times, American cops are far less successful at solving murders than their peers in other “rich nations” such as Australia, Germany and Great Britain. Their murder clearance rates are between seventy and ninety percent, while America’s is fifty-eight. One reason might be that the sheer numbers of murders in the U.S. overwhelms investigative resources. Most killings in the U.S. are also committed with guns, enabling assailants to keep their distance. And many involve gang members, thus minimizing the availability of willing witnesses.

3/15/22 In 2013 Illinois enacted a law that authorizes paying to relocate witnesses of violent crimes who fear that their testimony would place them at risk. But until (Blue) Gov. J.B. Pritzker recently suggested putting $20 million in the kitty, it’s never been funded. If the money is included in the approved budget, it would be dispensed to prosecutors by the State. “This is a perfect example of Democrats being tough on crime,” crowed a (Blue) legislator. “You can’t ask for a better scenario.”

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Turn Off the Spigot Lying: The Gift That Keeps on Giving

|