|

Posted 7/15/11

“TEACHING” POLICE DEPARTMENTS?

THAT’S RIGHT, TEACHING

Medical education is advanced as an appropriate model for the police

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. The 2011 NIJ Conference was full of surprises, most good, a few not so much. But of the sessions attended by your blogger, none proved a bigger head-scratcher than “Teaching Rounds in Police Departments,” which promoted the notion that adopting the model of a teaching hospital would lead to great improvements in the practice of policing.

In the first two years medical school is like school anywhere, mostly lectures. Hands-on training takes place during the third and fourth years, when students rotate through departments at a teaching hospital. It’s by observing experienced physicians, participating in examinations and, later, discussing the cases that budding doctors learn their craft.

Click here for the complete collection of resources, selection & training essays

This model is the basis for the Teaching Police Department Initiative, or TPDI. It’s planned that the Providence Police Department will become a “teaching police department,” akin to a teaching hospital, where managers from PPD and exchange students from other agencies will collaboratively develop “innovative police department organizational designs, operating policies/procedures, and performance measurement tools.” Roger Williams University’s Justice System Training and Research Institute will direct the program and provide academic support with assistance from two partners, the Brown University Medical School and the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

How Providence PD and Roger Williams came to be chosen we’ll come to later. But it’s clear that this is an exceptionally ambitious program. COPS Director Bernard Melekian, whose office will oversee the study, feels that the medical model is an excellent fit for getting police not just in Rhode Island but around the country to adopt “values-driven” and “evidence-based” cultures. As a former police chief, he is convinced that case studies and a “problem-based” learning approach will create “communities of practice” in which collaboration and experimentation are the norm.

Not everyone at the session seemed equally convinced. Technological and medical advances have come a long way in helping physicians diagnose ailments and prescribe and evaluate treatments. Police, on the other hand, still wallow in the subjective. Fixed rules and approaches often prove useless or counterproductive. Time and information, the two critical prerequisites for making good decisions, are in pitifully short supply. Hostile “clients,” uncertain settings and the absence of peer support may be strangers to a teaching hospital, but they’re a routine component of everyday policing.

Academies do what they can to prepare cops for the real world. One of the most ambitious and long-standing approaches is that of the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, which uses elaborate scenarios and paid role players to simulate field conditions. But even the best exercises can’t start to approach the realism of a teaching hospital, where students administer to real patients under the watchful eyes of medical faculty. Police academies try to bridge the gap between theory and practice by sending students on ride-alongs. It’s only superficially like doing “rounds,” but it’s as close to it as pre-service officers are likely to get.

Police management training much more closely resembles the approach that TPDI favors. Courses for law enforcement managers and executives are offered by state and regional police academies, the FBI, universities including Northwestern and Michigan State, the IACP’s Center for Police Leadership and Training, and PERF’s Senior Management Institute for Police. Case studies and collaboration have been core aspects of such programs for decades. There are also plentiful police groups at the local level. One example from Los Angeles, the South Bay Police Chiefs Association, hosts regular get-togethers where police managers explore issues of mutual concern. A countywide Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee, with representatives from local, state and Federal agencies serves essentially the same purpose.

Police training and interagency collaboration have reached a high level of maturity. As the NIJ sessions made perfectly clear, deep thinking and experimentation are very much alive and well in policing. Indeed, now that proposed cutbacks in Medicare and Medicaid threaten the viability of teaching hospitals, one could return the favor and offer the cops as a model for, say, medicine.

Excepting, of course, that the environments of policing and doctoring are different. While the ultimate law enforcement metric, the incidence of crime, resembles a medical outcome, there is no unique, agreed-upon path to curing social ills. American policing is by purpose and design an intensely local enterprise that’s carried out by upwards of twenty-thousand agencies. As James Q. Wilson pointed out in his seminal volume, Varieties of Police Behavior, agencies might share similar goals, but it’s communities that determine how officers go about doing their job. Norms differ, and what’s acceptable in one place may be deemed excessively intrusive in another.

It’s on such shoals that TPDI ultimately runs aground. To designate a police department as a “teaching” site elevates it above its peers and gives it great leverage to set the agenda. That can present a problem for other agencies, if for no other reason than the values, concerns and political climate of their communities may differ. Police chiefs ignore who they work for to their peril.

That lesson was recently driven home in, of all places, Providence. On June 22nd., only two days after the NIJ “teaching rounds” session, Providence police chief Dean Esserman abruptly announced his resignation. He was leaving, he said, due to fallout from allegations that minors drank alcohol at his daughter’s graduation party. To some his explanation rang hollow. Last fall three mayoral candidates announced that if elected they would fire him. He managed to hang on, but without a contract. Miffed by his brusque style (he recently got a day off without pay for berating a sergeant) and a generous compensation package (it was reportedly worth $331,154) officers returned a vote of no confidence. Esserman’s unenviable situation was summed up in a pithy headline a few days after his departure: “Outside the Providence Police, Dean Esserman was the idea man. Inside, he found little acceptance.”

Esserman was full of ideas. No less authoritative a source than Roger Williams University described TPDI as his “brainchild.” Interestingly, TPDI wasn’t funded in the usual manner but through a $750,000 earmark (some might call it pork) courtesy U.S. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D – RI). Apparently the university will actually get $474,000, so it’s assumed that DOJ, which is responsible for writing the checks, will retain a chunk and share the rest with its partners.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Your blogger, a retired Fed, is loath to criticize anyone for accepting Federal bucks. After all, it was only yesterday that taxpayers bought him a frozen yogurt (orange 50/50, his favorite.) But a jinx seems to have accompanied Roger Williams’ loot. In May it was announced that a budgetary shortfall could force America’s first “teaching police department” to lay off as many as 80 officers, or 17 percent of the force. So far, though, the only hammer that’s fallen is on the chief.

Well, the Colonel may be gone, but his three-quarter million dollar kid is still around. Joan Sweeney, TPDI’s co-director, emphasized that for the program to work Providence cops must be full partners. Sounds good, but considering just how irritated they must be with their ex-chief and all his notions, we’re not sure we’d like to be in that patrol car when it leaves the station.

UPDATES (scroll)

1/17/25 Just published in Criminology & Public Policy, an assessment of police training academies criticizes the universal over-emphasis on traditional officer-warrior aspects, such as the “rare instances” when lethal weapons must be used, while ignoring the “guardian-based” approach that exemplifies community policing. Fixing that, according to the authors, would require “a complete and comprehensive reorientation of police recruitment and basic training.”

2/28/22 As the George Floyd imbroglio makes clear, officers must intervene when their colleagues misbehave. How that’s best done is the subject of a program at Georgetown University. “ABLE” teaches that officers are “humans who get tired and stressed and make mistakes,” and looks on colleagues as “helpers” on the alert for signs of personal troubles. Intervention is taught as a stepwise method that begins with questioning a colleague’s conduct and proceeds in stages to physical intervention.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Cops Aren’t Free Agents

Posted 05/01/11

NEW JERSEY BLUES

How is the Garden State responding to increased violence? By shedding cops.

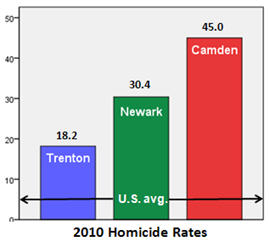

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. New Jersey’s disturbing uptick in homicide reportedly began last summer, when thirty-five persons were murdered in Newark in three months. New Jersey’s largest city (pop. 279,203) wound up with 85 murders in 2010, a disheartening rate of 30.4 per 100,000 population. That’s nothing new. In 2009, the most recent year for which national data is available, its homicide rate (28.7) was nearly six times the U.S. mean of 5.0.

Click here for the complete collection of resources, selection & training essays

Beset by gangs, drugs and guns, Newark is in deplorable shape. But it doesn’t hold a candle to Camden. Second only to St. Louis in serious crime among the nation’s 400 largest cities, the troubled community (pop. 79,980) closed 2010 with thirty-six homicides. Its murder rate of 45.0 was nearly half again Newark’s. One year earlier Camden’s rate was 43.0, nearly nine times the U.S. average.

Compared to its brethren, Trenton (pop. 82,609) seems like a safe place. After all, it had “only” 15 killings in 2010; its murder rate, 18.2, actually fell from 2009, when it was 20.6. That’s still more than

three times the national average and plenty sufficient to earn New Jersey’s capital a spot along with Camden and Newark in the most crime-ridden seven percent of American cities.

In 2010, following three years of improvement, New Jersey reported a thirteen percent increase in homicide, from 320 to 363, as murder trended up in a majority of counties. And things may be getting worse. Although optimists point out that violence in Camden hasn’t reached the levels experienced last summer (well, it’s not summer yet) it’s still up 17 percent when compared to the first quarter of 2010.

It’s a similar story in Newark, where twenty murders occurred during January-March, double the number (10) for the equivalent period last year. Aggravated assault increased two percent and robbery 11 percent. Burglary is up eight percent and auto theft jumped about a third.

So what’s being done? They’re laying off cops.

Bloodletting in the police ranks began in earnest last year when Atlantic City laid off 60 officers, 16 percent of its force. In December Newark PD lost 13 percent of its strength with a stunning 167-officer cut. This January Camden let go 163, slashing the troubled department by nearly half. (Forty-five superior officers were also demoted and put on patrol. A Federal grant has since let the city rehire fifty-five cops, but the funds are only expected to last a year.) And that’s not all. Only last month, just as a national police organization announced it was honoring Camden’s chief for innovating his way through the chaos (don’t ask), the city of Paterson cut 125 cops, one-quarter of its force.

All in all, it’s estimated that New Jersey has trimmed about 3,000 from its law enforcement ranks. With the state is in dire financial shape, few are expected to be replaced anytime soon. Unemployment, the loss of well-paying manufacturing jobs, sharp drops in property values, burgeoning public pension costs, declines in investment income and a host of other factors have brought the Garden State to its knees. And the problem may be getting worse. In March Governor Chris Christie announced that the lifelines traditionally extended to the state’s poorest cities – a stunning eighty percent of Camden’s budget comes from Trenton – would be cut $275 million, a full 17 percent.

You see, there’s urgent need for the loot elsewhere. Only days ago New Jersey was ordered to reimburse the U.S. $271 million in Federal tax funds that the state expended on a tunnel project it has since refused to complete. Interest on the debt, which New Jersey is contesting, amounts to a tidy $50,000 per week. Gov. Christie is refusing to raise taxes or restore prior tax cuts and suggests de-unionization and givebacks as a solution. Lacking that, letting public servants go is the only option.

When America’s founders chose to keep government close to the people they inadvertently set into motion a process that would inevitably consign poor citizens to poor public services. Wealth is unequally distributed. Local governments rely on property and sales taxes, and when economic downturns strike less affluent communities are hit the hardest. Paradoxically, they’re also the ones with the far greater need for police services in the first place.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

New Jersey’s cities may be an extreme example, but they’re not alone. We’ve all heard what’s been taking place in Detroit. Is it any wonder that the Motor City appears right next to Camden on CQ’s list? Scan the most crime-ridden municipalities and you’ll see one impoverished community after another. Flint, Michigan (100 officers laid off); Compton, Richmond and Oakland, California (80 officers laid off); Cleveland, Ohio (66 cops laid off); Gary, Indiana; Baltimore, Maryland. And yes, Washington, D.C. Then look at the opposite end of the list, where the safest cities are. Try to find a poor place, or any where a substantial number of cops have been let go.

Just try.

UPDATES (scroll)

3/10/25 On Friday evening, March 9, Newark PD Detective Joseph Azcona, 26, was shot and killed and his partner was wounded by a 14-year old boy who was wielding “an automatic weapon.” The officers were part of a joint local-Federal team that drove up to a group of youths who reportedly had illegal firearms. Return fire wounded the shooter. He was arrested and charged with murder and gun violations, and five companions were detained.

11/10/23 Trenton, New Jersey has an indisputable crime problem. And now, with the announcement of a “patterns and practices” investigation, its police have come under the Federal gun. According to DOJ, there are “serious and credible” allegations that officers stopped, searched and arrested pedestrians and motorists without sufficient legal basis, used force as punishment, and needlessly used force, or used it to excess, during routine encounters and with persons who were mentally ill.

2/27/21 During the last recession, Jersey City held firm and didn’t lay off any cops. New Jersey’s other major city, Newark, shed ten percent of its force in 2010. A recently published study of this “naturalistic experiment” by John Jay’s Eric L. Piza revealed that laying off cops led to significant increases in all forms of crime in Newark, and that the gap worsened over time.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED REPORTS

PERF report on impact of economic crisis on police services

RELATED POSTS

Is the Sky About to Fall? Cops Matter

Posted 2/3/11

WHICH WAY, C.J.?

Two John Jay scholars propose that

Criminal Justice programs emphasize methodology

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Normally we avoid quoting at length, but in this case it seems appropriate to let John Jay College’s Evan Mandery and David Kennedy have their uninterrupted say.

Students who seek careers as [criminal justice] practitioners must be familiar with the history and operation of the institutions they aim to serve. Aspiring policy makers must also be familiar with these institutions, but this knowledge is important not as an end in itself, but rather as a focal point to develop their analytical skills. For policy makers require a distinct skill set. They are increasingly demanded to have greater quantitative analytical capacity and, most importantly, to solve problems. Humanely educating aspiring police, correction and probation officers will always remain a core, and arguably the most important, function of criminal justice programs. But we believe in the coming decades, the burgeoning demand will be for critics, critical thinkers, original thinkers, problem solvers, innovators, curmudgeons, and reformers. Currently, this need is not met. (For the full article click here.)

What the authors seek is a “new sort of undergraduate” whose preparation will emphasize analytical skills rather than factual knowledge. Thus “empowered to think beyond the status quo,” students will sail forth to generate “original and ethical solutions to vexing social problems.” John Jay apparently intends to meld this alternative vision of criminal justice education into a bachelor of arts program. It will be offered alongside the college’s extant bachelor of science degree, which the authors describe as fulfilling the “historical mission of CJ education.”

Click here for the complete collection of resources, selection & training essays

There is no question that criminal justice education has significantly evolved. Your blogger’s undergraduate degree from Cal State Los Angeles, awarded in 1971, was in “Police Science and Administration.” Although the coursework had academic components, policing and corrections were taught by retired practitioners with master’s degrees. At a time when civil rights disputes and unrest over Vietnam threatened to unravel the social fabric, their preoccupation with the nuts-and-bolts of policing seemed beside the point. (For a remarkable 1969 report about conflicts between police and the public see “Law and Order Reconsidered”)

Your blogger and other students petitioned for a change. Our grievances were well received by some faculty, and in time the curriculum was transformed. Similar changes were happening elsewhere. By the late 1970’s baccalaureate criminal justice programs were abandoning narrow vocational orientations in favor of a more comprehensive, diagnostic approach. Students examined interactions within the criminal justice system and between the system and outside forces, studied the social, psychological and economic causes of crime, and explored the proper role of police in a democracy. Among the classic titles of the era are Herman Goldstein’s Policing a Free Society, William Muir’s Police: Streetcorner Politicians, and Peter Manning’s Police Work. These deeply analytical works addressed policing from a variety of perspectives, offering observations that hold true to the present day.

In 2005, after years of debate, the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences, a national organization of criminal justice educators, established a process for certifying criminal justice programs. Requirements were set out in six content areas:

- Administration of Justice: Contemporary criminal justice system, major systems of social control and their policies and practices; victimology; juvenile justice; comparative criminal justice

- Corrections: History, theory, practice and legal environment, development of correctional philosophy, incarceration, diversions, community-based corrections, treatment of offenders

- Criminological Theory: The nature and causes of crime, typologies, offenders, and victims

- Law Adjudication: Criminal law, criminal procedures, prosecution, defense, and court procedures and decision-making

- Law Enforcement: History, theory, practice and legal environment, police organization, discretion, and subculture

- Research and Analytic Methods: Quantitative - including statistics - and qualitative, methods for conducting and analyzing criminal justice research in a manner appropriate for undergraduate students

These guidelines and the accompanying standards purportedly represent the state of the art in criminal justice education. Yet they weren’t mentioned in the article by Mandery and Kennedy, which appeared in a publication of the American Society of Criminology, a competitor organization (Dr. Mandery has advised that he and Dr. Kennedy referred to and discussed the ACJS guidelines in detail but that the editors of The Criminologist, the ASC publication where the article appeared, unfortunately cut the material.) Your blogger, who referred to the ACJS standards while acting as outside reviewer of a local CJ program, found them clear, comprehensive and simple to articulate and defend. Actually, he had nowhere else to turn, as the ASC has not promulgated an equivalent.

To be sure, the ACJS guidelines do not articulate Mandery and Kennedy’s vision in its entirety. For example, there is nothing in ACJS about “teaching skills and critical thinking rather than facts” or the need for “intellectual discovery.” So what does ACJS favor? Here’s standard B.9:

The purpose of undergraduate programs in criminal justice is to educate students to be critical thinkers who can communicate their thoughts effectively in oral and written form. Programs should familiarize students with facts and concepts and teach students to apply this knowledge to related problems and changing situations. Primary objectives of all criminal justice programs include the development of critical thinking; communication, technology, and computing skills; quantitative reasoning; ethical decision-making; and an understanding of diversity.

Well, that sounds pretty good. Actually, the one clear distinction between ACJS standards and John Jay’s proposed baccalaureate is in the latter’s overarching emphasis on crunching numbers. While ACJS calls for instruction in quantitative and qualitative research “in a manner appropriate for undergraduate students,” Mandery and Kennedy emphasize the acquisition of statistical skills, with a capstone independent research project at the program’s conclusion.

Mandery and Kennedy briskly track the evolution of police strategies during the past decades:

New York City’s historic crime decline, and the perceived significance of its police force’s new operational approaches, gave credence to the ideas that police could reduce crime and should be held accountable for doing so. CompStat drove responsibility for crime outcomes down to geographic commands and raised the salience of data. As other police agencies adopted these innovations, and the Department of Justice sought to enhance the mapping capacity of police departments, the importance of data analysis was raised further. Soon it became more practicable to address hot spots, refine officer deployment, and identify crime trends.

If advanced data analysis really is that crucial, the need for a new curriculum should be self-evident. Yet the evidence that Mandery and Kennedy offer is hardly compelling. Mentioning Compstat and hot-spots in the same breath as New York City’s crime decline, part of a national trend for two decades, encourages the reader to assume that the former caused the latter. That’s a fallacy that should be evident to anyone versed in basic methodology. What’s more, crediting these “innovations” for bringing home the long-standing notion that police ought to be held accountable for crime is simply audacious.

As we said in Too Much of a Good Thing?, it’s not as though cops have been waiting for academics to come around to suggest the obvious. Once one peels away the rhetoric, “problem-oriented” and “hot spot” policing are nothing new. Open-air drug markets, street robberies (“muggings”), vehicle burglaries (“car clouts”) and other types of location-based offending were being addressed by special squads, directed patrol and covert surveillance well before your blogger joined the law enforcement ranks in 1972. Using data is also old hat. Pin-maps, then IBM punch cards and, finally, personal computers have tracked the incidence and place of crime for decades.

Yes, it’s become easier to collect, analyze and display information. But the benefits claimed by advocates of newfangled number-crunching techniques seem vastly overblown. “Putting a patrol car close to the action,” as a predictive policing experiment in Minneapolis seeks to do, sounds like a great idea, at least until it turns out in practice to mean within a mile of the next predicted crime. Even if the accuracy is increased, the chances that a patrol car will be available at the right time and place are slight. Reporting isn’t instantaneous, and unless a cop is perfectly situated offenders may be long gone. In cities of any size patrol officers already have a full plate. Beat cops constantly exchange information and are always on the lookout for known evildoers with whom to have a chat. Detectives, parole agents and probation officers also frequently pass down requests to watch for suspects, wanted persons and absconders from supervision.

Over-emphasizing numbers isn’t just beside the point – it can be a really bad idea. In Predictive Policing: Rhetoric or Reality? we discussed complaints by NYPD officers that pressures to look good under Compstat transformed measures into goals, forcing cops to make needless stops and arrests on pain of keeping their jobs. As we pointed out in the text and updates section of Liars Figure, a preoccupation with crime statistics reportedly led cops in various cities, including New York, Cleveland, Dallas, New Orleans, Baltimore and Nashville to not take reports or purposely downgrade offenses to make the numbers look good.

Since retiring from law enforcement your blogger has taught courses in research methods and policing. There is less crossover than one might think. Many pressing issues – misuse of force, lying to superiors, lying in reports and in court, mistaken arrests and other shoddy work, inadequate hiring standards, poor training, the lack of meaningful supervision, proliferation of guns, and so on – are not amenable to quantification other than in its crudest form; for example, by counting the number of officers fired for misconduct or killed by assailants each year. Others, such as racial profiling, present methodological complexities that can make it impossible to draw firm conclusions. Where numbers inarguably help – describing the incidence of crime, allocating and deploying resources – usually involves rudimentary techniques that should be readily comprehended by any reasonably bright undergraduate.

Except in its most trivial manifestations, quantitative research into policing has proven far less useful that what its proponents claim. One reason, we’re certain, is that researchers often fail to identify the proper variables or to develop accurate measures. “To cultivate creative and original thinking about one of the most challenging social problems of our time,” to borrow Mandery and Kennedy’s apt phrase, requires that everyone who wants to play in the sandbox – future practitioners and budding researchers alike – be exceptionally well informed about the environment of policing in its full, sausage-making complexity.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

And where would this knowledge come from? As we mentioned in R.I.P. Community Policing?, many scholars have published profound, illuminating descriptions of the police workplace. Alas, deeply probing, ethnographic research seems out of favor. (Yesterday I asked students in one of my classes whether anyone had read Varieties of Police Behavior. No one had.) Getting undergraduates to pore through the many great works sitting on library shelves may seem like a tall order. But if we’re really serious about preparing future cops and researchers that may be the best approach.

p.s. Here are a few classic titles:

Egon Bittner, Aspects of Police Work and The Functions of Police in Modern Society

Anthony Bouza, The Police Mystique

Herman Goldstein, Policing a Free Society

Peter Manning, The Narc’s Game and Police Work

John Van Mannen and Peter Manning, Policing: A View From the Street

Gary Marx, Undercover

William Ker Muir Jr., Police: Streetcorner Politicians

Albert Reiss, The Police and the Public

Larence Sherman, Scandal and Reform

James Q. Wilson, The Investigators, Thinking About Crime and Varieties of Police Behavior

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES

Quantity and Quality The Craft of Policing

RELATED POSTS

Cops Aren’t Free Agents Too Much of a Good Thing? Predictive Policing: Rhetoric or Reality?

A Very Dubious Achievement Liars Figure R.I.P. Community Policing

Slapping Lipstick on the Pig: Part I Part II Part III

|