|

Posted 8/1/23

PUNISHMENT ISN’T A COP’S JOB (III)

Some citizens misbehave. Some cops answer in kind.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. “Hi, um, I’m being followed by a police car.” According to the Los Angeles Times, those were the first words spoken by Emmett Brock when 9-1-1 answered his call. February 10 had turned out to be “a miserable day” for the high-school substitute teacher. A colleague harassed him for being transgender, and he left work early. On the way home Mr. Brock drove by a traffic stop. An L.A. sheriff’s deputy was being rude to a motorist. So he flipped him off.

Things turned decidedly sour. A sheriff’s patrol car promptly got on his tail. Mr. Brock said it was the same officer, but the deputy’s lawyer (yes, he now has one) denies it. Either way, the patrol car followed Mr. Brock turn by turn, though without activating warning lights or sounding its siren. Mr. Brock noticed its presence. Concerns over the deputy’s intentions supposedly led him to call 9-1-1 and convey what was happening. But the operator offered no help. And when Mr. Brock pulled into his intended destination, a 7-11, purportedly to buy a soft drink before going to his therapy appointment, so did the deputy. What happened was captured by the store’s external camera. (Audio from the deputy’s bodycam was subsequently inserted. Click here for the full video and here for our edited, captioned version with some slow-mo thrown in.)

Click here for the complete collection of conduct and ethics essays

Mr. Brock parked his vehicle and the deputy pulled in behind, blocking his exit. As Mr. Brock began to step out the deputy quickly walked up and got in his face. Their conversation isn’t perfectly clear, but the deputy apparently mentioned stopping Mr. Brock, and Mr. Brock countered “no, you didn't.” Things moved so quickly that even in slow-mo it’s impossible to say whether Mr. Brock tried to walk off. Or, as the deputy later claimed, made a fist. Nearly instantly, the deputy grabbed Mr. Brock’s left arm (see top sequence). Mr. Brock protested (“hands off of me”) and tried to free himself. But the deputy took him to the ground. And the fight was on. During the struggle Mr. Brock repeatedly complained that he was being hurt. But the deputy kept exerting force until he got his man in handcuffs. That took a couple of minutes.

Throughout, the officer clearly kept the upper hand. And fist. His report, which Mr. Brock’s lawyer provided to CNN, openly admits the use of considerable force: “I punched S/Brock face and head, using both of my fists, approximately 8 times in rapid succession.”

There’s no evidence that Mr. Brock committed a moving traffic violation, nor that he was ever signaled to pull over. So we can’t call what happened a “traffic stop.” But that’s how the officer characterized it, albeit after-the-fact. His purported justification was that an object (a deodorizer) hanging from Mr. Brock’s rear-view mirror obstructed his view of the roadway (see California Vehicle Code section 26708).

And no, we’re not making it up.

What happened near Circleville, Ohio on July 4th. was most definitely a traffic stop. And its justification seems clear. A highway inspector tried to stop a semitruck with a missing mudflap, but the vehicle’s operator, Jadarrius Rose, a 23-year old Memphis man, kept going. So the highway patrol stepped in. Mr. Rose pulled over for the troopers. An officer’s bodycam shows what then happened (for the full set of released bodycam videos, click here. For our edited, captioned version click here.)

That’s right: weapons were drawn and pointed at the truck. That, Mr. Rose told CNN, scared him. So, just like Mr. Brock, he dialed 9-1-1. And just like Mr. Brock, he didn’t find the operator’s comments sufficiently comforting. So he drove off.

Then things got a bit, um, complicated. According to Mr. Rose, the 9-1-1 operator eventually convinced him it was o.k. to pull over. So he did. But watch the video. During round #2 a veritable legion of squad cars joined what ultimately turned into a “three-county pursuit.” In his account to CNN, Mr. Rose said reassurances by 9-1-1 that he would be treated peacefully led him to stop. But an ABC News release, which is supposedly based on the official incident report, indicates that “troopers placed stop-sticks, or spike strips, in the roadway ahead of the chase and blew out Rose's tires, forcing him to pull over.”

That’s not an inconsequential difference. Still, Mr. Rose voluntarily stepped out of the cab and put his hands up (left image). But he apparently hesitated when ordered to get on his knees. A Circleville K-9 officer who had joined the chase walked up with his dog and ordered Mr. Rose to comply (second image). “You’re going to get the f***g dog. Get on the ground or you’ll get bit.”

From a distance, a bullhorn-equipped trooper saw what was happening. He repeatedly ordered the handler to not release his dog, as the suspect’s hands were up. Whether the handler heard him we don’t know. Either way, he promptly released the pooch. It initially ran off in the opposite direction, away from Mr. Rose (third image). It then stopped and turned. Although Mr. Rose had by then fallen to his knees, the handler nonetheless waved it back in (fourth image). The K-9 charged and grabbed Mr. Rose with its jaws. “I gave you three warnings, did I not?” the K-9 cop later scolded. “Did I not say final warning? Well, you didn’t comply, so you got the dog.”

Fortunately, Mr. Rose wasn’t seriously hurt. He faces felony charges for failure to comply with the troopers. As for the handler, he’s been fired.

Mr. Brock, a substitute high-school teacher, and Mr. Rose, a truck driver, were gainfully employed. Neither had a known criminal record. Yet both wound up losing their jobs. Their legal scars and unsought notoriety could also impair their future prospects. Of course, neither is fully blameless. “Flipping off” a cop and refusing to pull over are risky gambits, predictably laden with consequences. And we don’t just mean of the legal kind. In the “real” world where imperfect humans reside, rude challenges – including challenges to authority – often draw rude responses. “And the fight is on” isn’t just a catchphrase: it’s an accurate depiction of what one can expect when they disrespect the limits of human nature.

But officers are trained to keep their cool, right? After all, it’s hardly a secret that keeping the peace, enforcing the law and gathering evidence in chaotic, often hostile environments is no picnic. But the George Floyd imbroglio was a powerful reminder that techniques which are intended to keep the pot from boiling over (e.g., “de-escalation”) can’t always keep cops from getting emotionally caught up in the turmoil. And, as “Punishment (I)” and “Punishment (II)” warned, turn at least some into punishers.

So, what’s available? A solution that quickly comes to mind is to simply keep cops and citizens apart. Indeed, policymakers around the U.S. have moved to minimize the frequency of these encounters. Many jurisdictions abandoned aggressive enforcement practices such as stop-and-frisk. Others have prohibited cops from stopping cars for “technical” violations. In 2020, shortly after the George Floyd debacle, Virginia enacted a law that barred car stops for minor violations such as “dangling objects from rear view mirrors that obstruct a driver’s view”. In April, Minneapolis, the community at the epicenter of the troubles, signed a “court-enforceable agreement” with the Minnesota Dept. of Human Rights that severely circumscribes pretextual stops. Consent searches during such stops are prohibited. Use of force is also limited, and officers must not use it to punish or retaliate. What’s more, they will no longer be trained on “excited delirium”, a medically-recognized syndrome that’s caught blame for encouraging cops to physically (and needlessly) intervene.

That shift in tone, which we discussed in “Backing Off”, “Regulate. Don’t “Obfuscate” and “Full Stop Ahead”, has supposedly led to some unintended consequences. Police, law enforcement groups and more than a few local and state officials have warned that throttling back emboldens evildoers. Concerns that Virginia’s move made “roadways more dangerous” and “increased crime” recently led its legislators to introduce a bill that would return traffic laws to their former intrusiveness.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

In the end, we’re reluctant to endorse un-craftsmanlike approaches to policing. Such as letting cops manufacture reasons for stopping persons whose behavior stirs misgivings. So what should be the watchwords? “Articulable” and “reasonable.” When an officer’s suspicion that something is criminally amiss rises to that level, by all means, make the stop. If not, move on. Our personal experiences suggest that’s how most cops go about their jobs, every hour of every day. Unseemly digressions (e.g., Mr. Brock and Mr. Rose) are the exceptions. In fact, three years ago, our Police Chief magazine essay, “Why Do Officers Succeed?” suggested that successful episodes of policing could serve as excellent templates for doing it right. Here’s an outtake:

Officers are frequently involved in encounters that, had they not been adroitly handled, would have likely turned out poorly. They regularly meet substantial challenges when gathering evidence of serious crimes. These obstacles and others are overcome almost as a matter of course. Imagine the potential benefits to the practice of policing should we probe these happy outcomes to find out why officers succeed.

Still seems like a good idea.

UPDATES (scroll)

12/19/24 Los Angeles-area substitute teacher Emmett Brock was having “a miserable day” in August 2023. So as Sheriff’s deputy Joseph Benza III drove by, he flipped the cop off. Deputy Benza followed the transgender man into a parking lot, pulled him from his car and “violently body slammed” him to the ground. He handcuffed Brock and booked him on a felony. Benza had his colleagues lie about what happened, and Brock lost his job over the encounter. Local prosecutors refused to charge Benza, so the Feds stepped in. Benza just agreed to plead guilty to a felony civil rights violation. He faces up to ten years in prison. Meanwhile eight other deputies, including "several sergeants," have been relieved of duty for allegedly helping cover things up.

9/20/24 DOJ has launched a patterns and practices inquiry into Rankin County, Mississippi and its Sheriff’s Department. Its move follows on the guilty pleas and sentencing on Federal and State charges of five deputy members of a “Goon Squad” and a local cop, who tortured and savagely beat two Black residents for over an hour in January 2023. They are now serving terms ranging from ten to over forty years in prison. (See 3/22/24 update)

9/12/24 Dolphins player Tyreek Hill wishes he could have a do-over. “I will say I could have been better.” He admits he could have been more cooperative. But not letting down the window when ordered, he insists, was no reason for a Miami-Dade cop and his colleagues “to literally beat the dog out of me.” And he demands that the officer be fired. Hill, though, has reportedly been on the giving end of assaults. Click here and here for two examples. (See below update)

9/11/24 There’s no doubt that star Dolphins player Tyreek Hill was speeding when Miami-Dade County police

pulled him over outside Hard Rock stadium. But the cops didn’t recognize him, and his persistent refusal to roll down the window and

quietly cooperate quickly progressed to his extraction from the car, pinning to the ground and handcuffing. While Florida laws require that

occupants exit a vehicle if required, Hill’s treatment, which was captured on video, led to one officer’s suspension from street

duties while the agency investigates. Hill was soon let go and went on to do a great job that day. (See above update)

7/10/24 On July 4th. 2023 then-Northwoods, Missouri police sergeant Michael Hill dealt with an alleged problem-maker at a local Walgreens by having then-officer Samuel Davis haul him off to another town, deliver a frightful beating, and dump him on the side of the road. A passer-by soon came across the bloodied man, who told her what had just happened. He also sued. Both officers were promptly fired and charged with State crimes. They then lied to the FBI about what had taken place. DOJ has now stepped in with Federal civil-rights indictments that carry a potential life term.

3/22/24 Five former Rankin County, Mississippi deputies and a local police officer, all White, were sentenced to prison terms ranging from ten to forty years on their guilty pleas to violating the civil rights of two Black residents. According to prosecutors, the accused engaged in a “hate-fueled power trip” in which they burst into a home without a warrant, used racial slurs, delivered countless blows, and staged a mock execution in which one of the victims was shot in the jaw. Former deputies testified of a “goon squad” that took pride in abusing suspected criminals and ruled over promotions and assignments. (Se 9/20/24 update)

3/21/24 Emmett Brock lost his job as a substitute high school teacher because of his arrest by a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy one year ago. Violently subdued after a traffic stop (he flipped off the deputy while driving by), the transgender man was charged with “three felonies and a misdemeanor.” But bodycam video proved damning, and the prosecution was dropped. He’s now been fully exonerated. Mr. Brock has filed a lawsuit, and the D.A. is investigating the deputy.

12/4/23 A revised set of rules and mandating that deputies wear body cameras are two of the major correctives revealed by Rankin County (MS) Sheriff Bryan Bailey as he awaits the Federal and State sentencing of six White former deputies who participated in the unconscionable beating of two Black men last January. A $400 million lawsuit is in the works. (See below update)

8/4/23 and 8/15/23 Each

of the six White Rankin County, Mississippi officers who burst into a home in January and tortured and physically abused two Black men for over an hour have now pled guilty to multiple Federal and State felonies. Their sentences, which will run concurrently, could range up to life imprisonment. Among the charges are covering up the serious wounding of one of their victims, who was shot in the mouth when an officer play-acted his murder. Three of the defendants also pled guilty to the December 2022 abuse of a White man whom they were trying to get to confess. (See above update)

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES

Why Do Officers Succeed? The Craft of Policing

RELATED POSTS

Craft of Policing special topic

Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job (II) Backing Off

Regulate. Don’t “Obfuscate” Full Stop Ahead Another Victim: The Craft of Policing

Third, Fourth and Fifth Chances Fair But Firm Violent and Vulnerable

A Not-so Magnificent Obsession De-escalation: Cure, Buzzword or a Bit of Both?

Posted 6/30/23; edited 7/1/23

WATCHING THE WATCHERS

Will sanctioning its cops bring Minneapolis back?

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Not long before their Third District colleagues tangled with George Floyd, a couple of officers from Minneapolis PD’s Fourth District festooned the Christmas tree that graced their precinct's lobby with some unusual ornaments: “a pack of menthol cigarettes, a can of Steel Reserve malt liquor, police tape, a bag of Takis snacks and a cup from Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen.” Described as “super racist stuff” by Mayor Jacob Frey, these unusual decorations upset more than a few citizens. And ultimately led to the suspension of one of the cops, the retirement of his partner, and the demotion of two of their bosses.

As one might expect, the incident was juicy fodder for the media. But it didn’t hold a candle to the tragedy that came five months later. And one year after that, on the day following the conviction of ex-MPD cop Derek Chauvin for murdering Mr. Floyd, the Department of Justice launched a “patterns or practices” investigation of Minneapolis P.D. Its recently released report paints a grim picture of how MPD officers treated citizens, and particularly members of racial and ethnic minorities. According to Attorney General Merrick Garland, MPD officers “routinely disregard the safety of people in their custody” and “fail to intervene to prevent unreasonable use of force by other officers.” They reportedly mistreat persons suffering from behavioral disorders, violate free-speech rights, and discriminate against Black and Native American persons. (And yes, those Christmas ornaments get prominent mention. See pg. 46.) Here’s an extract from the report’s opening page:

For years, MPD used dangerous techniques and weapons against people who committed at most a petty offense and sometimes no offense at all. MPD used force to punish people who made officers angry or criticized the police. MPD patrolled neighborhoods differently based on their racial composition and discriminated based on race when searching, handcuffing, or using force against people during stops.

Click here for the complete collection of conduct and ethics essays

George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020. Our initial account, “Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job,” was posted on June 3rd. Three weeks later we followed up with an in-depth assessment of poverty and crime in Minneapolis. Focused on the year preceding the tragic encounter, our analysis revealed a profound relationship between income, race and violence. A comparo between four neighborhoods at each end of the violent crime continuum reflected what we’ve found elsewhere: as prosperity increases, so does the proportion of White residents. Meanwhile violence goes down.

Of course, the link between poverty and violence is well known. Our neighborhoods essays frequently roll out data illustrating that relationship throughout urban America. And cops must deal with the consequences every day. Minneapolis’ economic disparities were no secret to the authors of DOJ’s report (pp. 3-4):

The metropolitan area that includes Minneapolis and neighboring St. Paul known as the Twin Cities has some of the nation's starkest racial disparities on economic measures, including income, homeownership, poverty, unemployment, and educational attainment… The median Black family in the Twin Cities earns just 44% as much as the median white family, and the poverty rate among Black households is nearly five times higher than the rate among white households…

According to DOJ, Black and Native Americans aren't simply poorer. They’re also far more likely to be stopped by police. A graph shows that MPD makes proportionally fewer traffic enforcement stops as the proportion of White residents increases (pg. 34). Neighborhoods “with fewer white people” are reportedly beset by pretextual stops that MPD uses to find guns and combat violence. Searches of Black persons are disproportionately frequent. Race and ethnicity aside, the role of place doesn't come up until page 40, when it's reported that officers in two of the city's five police precincts use far more force against Blacks and Native Americans than against Whites during stops: Neighborhoods “with fewer white people” are reportedly beset by pretextual stops that MPD uses to find guns and combat violence. Searches of Black persons are disproportionately frequent. Race and ethnicity aside, the role of place doesn't come up until page 40, when it's reported that officers in two of the city's five police precincts use far more force against Blacks and Native Americans than against Whites during stops:

For example, from May 25, 2020, to August 9 , 2022, in the Third Precinct where many Native Americans live and where supervisors told us the cowboys want to work MPD used force 49% more often during stops involving Black people and 69% more often during stops involving Native American people than they did during similar stops involving white people. And during that same period, officers in the predominantly white Fifth Precinct used force against Black people 44% more often than against white people during similar stops.

Still, other than noting that “MPD has often used a strategy known as ‘pretext’ stops to address crime,” (p. 34), the report was mum about what that “crime” actually looks like. Offending and its distribution across the city get no mention. In a report that ostensibly seeks to assess why Minneapolis’ cops act as they do, the quantity and nature of the criminal incidents to which they respond would seem pertinent. But they’re ignored.

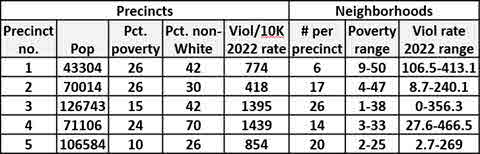

A thorough reckoning of the environment in which Minneapolis cops labor was clearly not part of DOJ’s game plan. But it’s what we set out to do. Minneapolis’ five police precincts (“Districts”) service eighty-seven neighborhoods. Leaving aside the University of Minnesota and three industrial areas, we collected data on eighty-three. Demographics are from the city’s official “demographics dashboard”. Crime data is from the “crime dashboard.” We downloaded data on all crimes between January 1, 2019 and June 15, 2023 that were coded as murder/non-negligent manslaughter, aggravated assault, robbery, and kidnapping. Our process produced unofficial violence rates per 10,000 population. This table summarizes the findings:

Minneapolis’ five precincts exhibit dramatic differences in economics and violent crime. The First, Second and Fourth have overall poverty rates that are more than twice those of the privileged Fifth. Yet the Fifth nonetheless sports a substantial violence rate. Looking within, it turns out that three of its neighborhoods (Lyndale, Steven’s Square and Whittier) are burdened with poverty scores in the twenties. These and other within-precinct differences led us to set them aside and focus on neighborhoods.

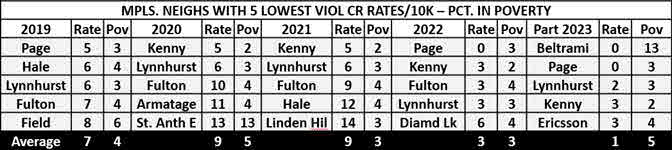

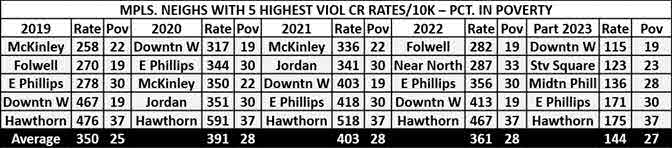

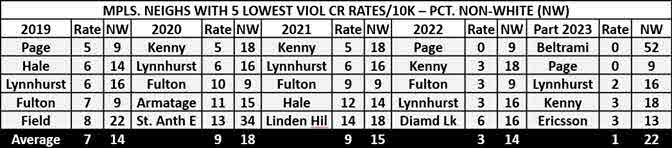

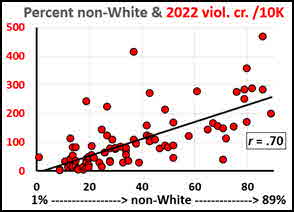

Our present inquiry covers the period between 2019 and June, 2023. We begin with yearly comparisons of five neighborhoods at each end of the violence spectrum. (For 2023 that’s a part-year rate). Lowest-violence neighborhoods are depicted in the top table, and highest-violence neighborhoods are in the bottom table. Each is coded for violence rate and percent of residents in poverty. Their differences - and its consistency - is truly astounding. Violence and poverty are literally locked in an embrace. (According to the 2021 ACS, Minneapolis’ citywide poverty rate was 15%).

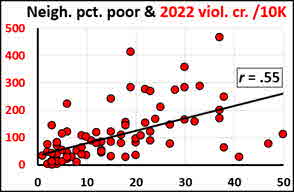

This scattergram depicts the relationship between percent in poverty (horiz. axis) and 2022 violent crime rate (vert. axis) for the 83 neighborhoods under study (each is represented with a red dot). The “r” statistic ranges from zero, meaning no relationship, to one, which means that the variables (percent poor and the violent crime rate) are in perfect sync. While there are outliers, that r of .55 reflects a pronounced tendency for poverty and violence to go up and down together. This scattergram depicts the relationship between percent in poverty (horiz. axis) and 2022 violent crime rate (vert. axis) for the 83 neighborhoods under study (each is represented with a red dot). The “r” statistic ranges from zero, meaning no relationship, to one, which means that the variables (percent poor and the violent crime rate) are in perfect sync. While there are outliers, that r of .55 reflects a pronounced tendency for poverty and violence to go up and down together.

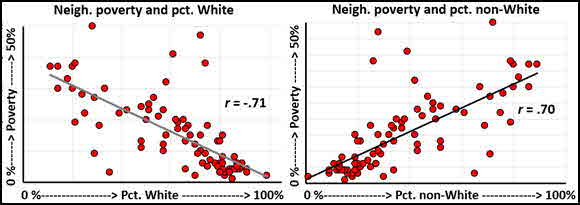

DOJ’s report complains that MPD officers unjustly pick on non-Whites. But could other factors be contributing? Say, higher rates of violence in lower-income neighborhoods? Below are repeat comparos between low and high-violence neighborhoods, but with percentage of non-White residents instead of poverty rates.

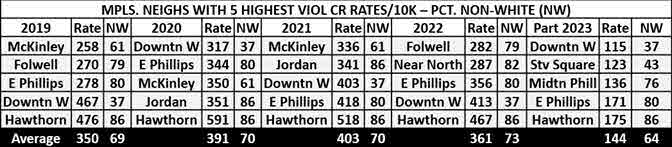

Again, there are exceptions. Note, for example, Beltrami’s zero violence score in 2023. But violent crime rates clearly trend high where non-Whites abound. Check out the scattergram. At r = .70 the relationship between violence and percent non-White is undeniably pronounced. Again, there are exceptions. Note, for example, Beltrami’s zero violence score in 2023. But violent crime rates clearly trend high where non-Whites abound. Check out the scattergram. At r = .70 the relationship between violence and percent non-White is undeniably pronounced.

We don’t argue that some Minneapolis officers shouldn’t be wearing a badge. There’s a reason why our original post about George Floyd, which came out one week after the incident, was entitled “Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job.” Yet considering poverty’s relationship with violence, ignoring its role does no one any favors. And in Minneapolis, the economic circumstances of many non-Whites are indeed bleak:

Not-so-incidentally, that intimate connection between poverty and violence, which the Feds ignored, is no secret to Minneapolis’ residents. We regularly update “Don’t ‘Divest’ – Invest!”, our follow-on essay about George Floyd, with relevant news clips about the troubled city. Here’s a sampling (most recent first):

- 5/5/23 Violence-ridden Minneapolis is beset by three street gangs: the “Lows,” the “Highs”, and the “Bloods”. On May 3 DOJ unsealed indictments charging thirty members of the “Highs” and the “Bloods” with a RICO conspiracy to commit murder and robbery and to traffic in drugs. Fifteen additional members are charged with Federal gun and drug violations. A like indictment naming the “Lows” is anticipated

- 12/22/22 Residents of a subsidized apartment complex in Minneapolis’ working-class Cedar-Riverside neighborhood blame an “explosion of Fentanyl” and a profusion of homeless encampments for break-ins and shootings that have made life unpleasant and all-too-often, treacherous. Despite hiring a security guard and adding more cameras, “I'm just not sure we're making up any ground,” says a property manager. “Every night there's something new.”

- 8/27/22 Black people account for about 19 percent of Minneapolis residents. Yet 83 percent of shooting victims so far this year have been Black, as have 89 percent of known shooters. “That makes sense,” said City Council member LaTrisha Vetaw, who is Black, as the shootings are taking place in “underserved communities” predominantly inhabited by Black persons.

- 8/5/22 Minneapolis’ “Downtown West,” a busy district with concert venues and official buildings, enjoyed a reprieve from crime as activity decreased during the pandemic. But as things get back to “normal,” crime and violence have returned with a vengeance. So far this year violent crime is 25 percent higher than in 2021, gunfire is up 40 percent, and property crimes have soared 65 percent. Police staffing, though, is way down; the downtown precinct has 49 only cops on patrol versus 81 in 2020.

Full stop. As that May 5, 2023 update suggests, not everyone in DOJ has focused their angst on the cops. Check out its recent announcement about the Federal indictment of dozens of Minneapolis gang members who wreaked havoc in the city’s impoverished neighborhoods: “The most vulnerable in our communities are often those most impacted by gun violence and criminal gang activity. Our most vulnerable residents are entitled to the same protections and safety as everyone else in society.”

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Still, whether it’s police or the Feds, law enforcement is inevitably after-the-fact. Even when well done it’s often too little, too late. What’s really necessary is what we’ve called on for the last decade-and-a-half. Here’s our favorite outtake from “Fix Those Neighborhoods!”:

Yet no matter how well it’s done, policing is clearly not the ultimate solution. Preventing violence is a task for society. As we’ve repeatedly pitched, a concerted effort to provide poverty-stricken individuals and families with child care, tutoring, educational opportunities, language skills, job training, summer jobs, apprenticeships, health services and – yes – adequate housing could yield vast benefits.

That’s an issue that cuts across national boundaries. Consider the current turmoil in France, which is beset by riots and looting that were sparked by the July 27 police shooting death of a 17-year old who tried to drive off after a traffic stop. His killing, in a poverty-stricken area of the Paris suburb of Nanterre, was “the lighter that ignited the gas. Hopeless young people were waiting for it. We lack housing and jobs, and when we have (jobs), our wages are too low.” Those were the words of a resident of nearby Clichy, where a notorious 2005 police encounter led to the deaths of two poor youths and set off weeks of rioting. A decade-plus later, France would break out in riots sparked by the murder of George Floyd. According to the New York Times, “France is fractured between its affluent metropolitan elites...and low-income communities in blighted, racially mixed suburbs where schools tend to be poor and prospects dim.” French police killed 13 motorists in 2022 and three including the youth this year; the officer who shot him was promptly arrested and charged with homicide.

To be sure, cops differ. “Third, Fourth and Fifth Chances” emphasized that troubled officers require prompt attention. (Derek Chauvin isn't the first MPD officer whose dodgy conduct was overlooked until it was too late. Check out “A Risky and Informed Decision”, our 2021 piece about ex-cop Mohamed Noor.) So by all means, don’t abandon sincere efforts at police reform. But keep in mind that they're no substitute for the funding and hard work that are urgently needed to restore sanity to low-income neighborhoods.

And we don’t just mean in Minneapolis.

UPDATES (scroll)

8/5/24 For the third consecutive year Minneapolis P.D. and its state and Federal partners are conducting a week-long enforcement effort at designated “crime hotspots” in the crime-beleaguered city. Its primary goal - seizing illegal firearms - seems on track, with 13 gun seizures during the project’s first two days. Last year the program netted 38 guns and 100 arrests. Police acknowledge that their efforts can’t fully resolve the problems that besiege the hot spots. “We recognize that...long-term solutions involve more than just arresting people. That’s beyond the scope of what we do.”

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Special topics: Craft of Policing Neighborhoods George Floyd

Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job Third, Fourth and Fifth Chances A Risky and Informed Decision

Fair But Firm Fix Those Neighborhoods! Don’t “Divest” – Invest!

Posted 2/20/23

PUNISHMENT ISN’T A COPS JOB (II)

In Memphis, unremitting violence helps sabotage the craft

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. During the evening hours of January 7, Memphis Police Department’s “Scorpion” anti-crime unit set the stage for yet another memorial to police abuse. A few days later, after Tyre Nichols died from his injuries, residents adorned the spot of his final encounter, transforming a residential streetcorner into an ode for a twenty-nine year old California transplant whom few had really known.

That place, the intersection of Castlegate and Bear Creek lanes, was where officers intercepted Mr. Nichols after he fled from their colleagues. His first encounter, at Baines and Ross Roads, where authorities say they stopped him for reckless driving, was captured by a pole-mounted camera and the bodycam of a late-arriving cop. (Click here for our condensed version of the video.)

Click here for the complete collection of conduct and ethics essays

Unfortunately, that’s the only video that’s been released of that first stop. So we can’t tell whether there really was a pressing, let alone legitimate reason to make the stop. Nor whether Mr. Nichols, who is depicted being dragged out of his car by an angry, cursing cop, had really refused to peacefully exit the vehicle.

All along, Mr. Nichols speaks calmly. But he evidently offered some physical resistance, and the officers used pepper-spray and a Taser (third image). Even so, Mr. Nichols quickly managed to break free and run off (fourth image).

As members of a special team, the officers who made the stop were in an unmarked car. That could have worried Mr. Nichols from the start. Their aggressiveness and crude language may have also come as a shock. We don’t know whether Mr. Nichols was under the influence of drugs, leading him to be uncooperative and combative, such as what’s been attributed to persons in the throes of “excited delirium.” Police later asked Mr. Nichols’ mother if her son was on drugs, as he had displayed “superhuman strength” when they tried to apply handcuffs. But she said that the tall, skinny man suffered from Crohn’s disease. That’s a substantial disability. And during the struggle at the first stop location, one of the cops got accidentally hit with pepper-spray (click here for a brief clip that depicts the officer’s partner rinsing out his eyes.) That dousing might have relaxed the cops’ grip on Mr. Nichols.

Whatever enabled the man’s escape, the initial encounter demonstrates a lack of tactical aptitude. Contrast that with what happened at the start of the disastrous incident after which this essay is entitled, the murder of George Floyd, when a rookie cop got the drug-addled man out of his car, in handcuffs and on the sidewalk without causing him any harm. Floyd’s supposedly drug-induced “superhuman strength” came later, when he violently resisted being seated in a police car. (See the testimony of MPD Lt. Johnny Mercil and MPD medical support coordinator Officer Nicole Mackenzie during Chauvin’s trial).

Once he broke free, Mr. Nichols hot-footed it to his mother’s house. It’s located in one of Memphis’ nicer areas, about a half-mile away. Alas, another Scorpion crew caught up with him as he entered the neighborhood. That encounter, which involved twice as many cops as the first, was grotesquely violent

from the start, with officers mercilessly kicking and pummeling Mr. Nichols (left image) and repeatedly dousing him with pepper spray (right image). About six minutes later, once Mr. Nichols was virtually

unresponsive, they dragged him away (left image) and propped him against one of their cars (right image.) (Click here for our condensed version of the polecam video, and here and here for our condensed versions of officer bodycam videos.)

Most of our information came from the videos and the veritable flood of news coverage. (Click here for the Associated Press Nichols “hub”, with links to each of their stories.) Other than the videos, little has been officially released. On January 20, two weeks after the encounter, Memphis PD Chief Cerelyn “CJ” Davis posted a brief notice announcing the firing, earlier that day, of the five officers who encountered Mr. Nichols at the streetcorner. One week later she delivered a video address. Her remarks (click here for a transcript) implicitly attributed their “egregious” behavior for his death. Calling her cops’ conduct “heinous, reckless and inhumane”, a violation of “basic human rights” and “the opposite” of what they were sworn to do, she promised “a complete and independent review…on all of the Memphis Police Department's specialized units.” (According to the AP, as of February 7 six Memphis officers have been fired over the incident and a seventh was removed from duty.)

Still, the Chief didn’t say that police were solely to blame for the horrific outcome:

I promise full and complete cooperation from the Memphis Police Department with the Department of Justice, the FBI, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, and the Shelby County District Attorney's office to determine the entire scope of facts that contributed to Tyree Nichols death.

So far, none of these agencies have released their reports. Shelby County’s Coroner is also yet to publicly weigh in. However, according to a lawyer retained by the Nichols family, “preliminary findings” issued by “a highly regarded, nationally renowned forensic pathologist” revealed that Mr. Nichols “suffered extensive bleeding caused by a severe beating.” Whether drugs or a prior medical condition might played a role in his death is yet to be announced.

Medical issues aside, did Mr. Nichols’ behavior during the initial stop make things worse? A police report filed by the “Scorpions” supposedly stated that Nichols was a suspect in an aggravated assault, that he was “sweating profusely and irate” when he got out of the car, that he grabbed for an officer’s gun, and that he pulled on the cops’ belts (ostensibly, to get a gun). But nothing was said about the officers’ use of force. Really, given the horrific police conduct captured on the videos, Mr. Nichols’ physical condition and behavior now seem beside the point. Fundamentally, we have a replay of another shameful saga. Had Derek Chauvin not forcibly held him down for those infamous six minutes, a man who had committed a (minor) crime, who did have drugs in his system, and who did exhibit seemingly “superhuman strength” would have come out alive.

Had the Memphis cops not savagely beat Mr. Nichols, he, too would have unquestionably survived. But they did. So were they rogues from the start? Demetrius Haley, the officer who pulled Mr. Nichols from his car, was a former prison guard. Three years before becoming a cop he reportedly participated in a “savage beating” that led to a Federal lawsuit. Yet Memphis hired him anyway.

“Three (In?)explicable Shootings” and “Black on Black” discuss other encounters between Black cops and Black citizens that ended poorly. But our essays are cluttered with examples of “easily rattled, risk-intolerant, impulsive or aggressive” White cops as well. And their deficiencies were often no secret. Consider the Minneapolis cop who shot and killed a 9-1-1 caller for the “crime” of walking up to his car. Not only did he stack up serious complaints during his first two years on the job, but his fitness to be a cop was questioned by psychiatrists when he was hired. And there’s the tragic November 2014 shooting of Tamir Rice, a 12-year old Cleveland boy. He was gunned down by a rookie who had been pressed to resign by his former agency. Here’s what that department’s deputy chief said:

He could not follow simple directions, could not communicate clear thoughts nor recollections, and his handgun performance was dismal…I do not believe time, nor training, will be able to change or correct the deficiencies…

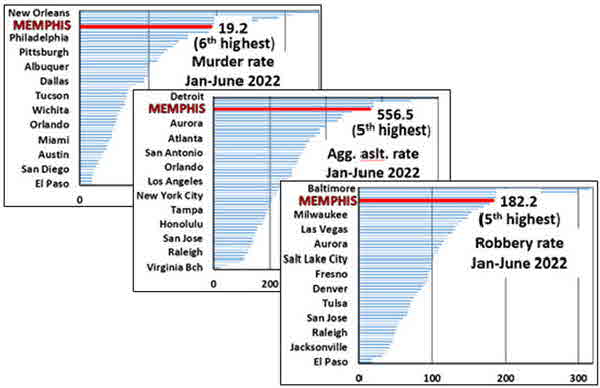

How did “the craft of policing” sink to the level displayed by the “Scorpions”? Let’s start by assessing a central feature of the police workplace: crime. According to a recent survey by the Major Cities Chiefs Association, here’s where Memphis sat, violent crime-wise, during the first six months of last year:

(MCCA reported data for seventy agencies, but we only calculated crime rates per 100,000 pop. for the sixty metropolitan police departments whose population base could be readily determined. Also remember that these are six-month rates).

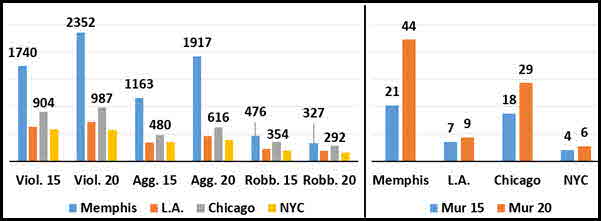

Memphis’ violent crime problem is nothing new. Turning to the UCR, here’s how its 2015 and 2020 full-year crime rates compared with our “usual suspects” (L.A., Chicago and New York City):

Again, these are rates per 100,000 population. Their underlying frequencies are also very revealing. For example, Memphis (pop. 657,936) reported 135 murders and 11,449 violent crimes in 2015. Los Angeles (pop. 3,962,726), a city six times in population, suffered twice as many murders (282) and a bit more than twice as many violent crimes (25,156).

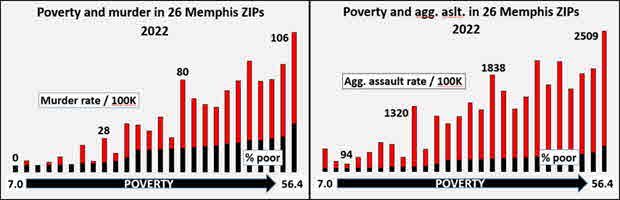

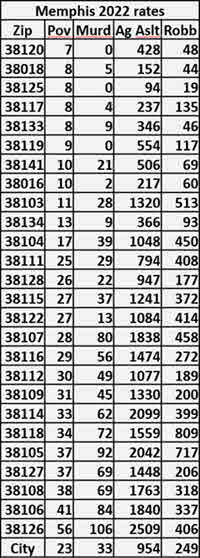

And it gets worse within. Drawing violent crime data from the Memphis hub, and poverty data from the Census, we calculated full-year, per/100,000 rates for murder, aggravated assault and robbery for each of the city’s twenty-six unique ZIP codes. We used correlation (the “r” statistic) to assess the relationships between poverty and crime (“r” ranges from zero to one: zero means no relationship, one denotes a lock-step association):

These r’s suggest that poverty, murder and aggravated assault are essentially two sides of the same coin. And robbery isn’t far behind. These sobering messages are also conveyed by the graphs and the table (both list Zip’s by poverty, from low to high):

Prior essays, most recently “What’s Up? Violence” and “Woke Up, America!”, emphasized the criminogenic effects of poverty. “Fix Those Neighborhoods!” pointed out that cities need lots of “prosperous neighborhoods” to keep their overall violence stat’s down. With nearly one in four residents in poverty, that’s where Memphis falls decidedly short. Its 2022 citywide murder rate, a nasty 33, is higher than the rates of LAPD’s notoriously violent 77th. Street Division (pop. 175,000), which came in at 30, and NYPD’s chronically beset 73rd. precinct (pop. 86,000), which scored an extreme (by Big Apple standards) 26. Indeed, the 37 per 100,000 rate where Mr. Nichols’ first encounter with police took place – Raines & Ross roads, Zip 38115 – is one of eleven that exceed the city’s overall 33; and most, by comfortable margins (38126, where more than half live in poverty, scored a soul-churning 106.) Prior essays, most recently “What’s Up? Violence” and “Woke Up, America!”, emphasized the criminogenic effects of poverty. “Fix Those Neighborhoods!” pointed out that cities need lots of “prosperous neighborhoods” to keep their overall violence stat’s down. With nearly one in four residents in poverty, that’s where Memphis falls decidedly short. Its 2022 citywide murder rate, a nasty 33, is higher than the rates of LAPD’s notoriously violent 77th. Street Division (pop. 175,000), which came in at 30, and NYPD’s chronically beset 73rd. precinct (pop. 86,000), which scored an extreme (by Big Apple standards) 26. Indeed, the 37 per 100,000 rate where Mr. Nichols’ first encounter with police took place – Raines & Ross roads, Zip 38115 – is one of eleven that exceed the city’s overall 33; and most, by comfortable margins (38126, where more than half live in poverty, scored a soul-churning 106.)

So what’s our point? Prosperity can give cops a relatively peaceful environment in which to ply their craft. But there’s precious little prosperity or peace in Memphis, a city literally awash in violence. It’s that carnage that in November 2021 led the police chief to deploy teams – they were impolitically named “Scorpion” – to conduct what are essentially stop-and-frisk campaigns. As one might have expected, their aggressive posture quickly generated blowback. That’s not unlike what similar projects encountered elsewhere. “A Recipe for Disaster” and “Turning Cops Into Liars” described the travails of LAPD’s Metro teams, which focused on violence-ridden “hot spots”. Its members were repeatedly accused of making needless stops, using excessive force, and justifying their unseemly behavior by lying on reports. Like issues long plagued the L.A. County Sheriff’s Dept., which continues struggling with “deputy gangs.” Similar problems have beset anti-crime campaigns in Chicago, New York City and elsewhere. Some of these programs were disbanded, but surges in violence that accompanied the pandemic brought many back.

What happened in Memphis may not be unique. Its exhaustive visual documentation, though, is one for the record books. What’s more, it wasn’t just one or two cops, who could be blamed as outliers. So far, more than a dozen officers (including two Shelby County deputies) have been implicated in the brutal episode. Their “job done” nonchalance after pummeling Mr. Nichols – they mill about exchanging casual talk – fits that “culture of violence and bravado” which the head of Memphis’ NAACP chapter, Van Turner, believes has infected policing throughout the U.S. As we watched the videos, the thrashing conveyed an angry fusion reminiscent of how George Floyd was treated after he fought the cops. Punishing someone with a merciless beating, as in Memphis, or by relentlessly pinning them to the ground and ignoring their pleas, as in Minneapolis, really is “two sides of the same coin.”

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

What’s to be done? As usual, police executives have taken to rulemaking. A recently enacted LAPD regulation prohibits pretextual stops unless officers have “articulable information” that a citizen’s behavior could lead to serious injury or death. And there’s Chicago PD’s 5,777 word foot-chase policy, whose complexities led the police union to (justifiably, we think) characterize it as a “no-foot-chase” policy.

Of course, limiting stops and chases will keep some terrible things from happening. Perhaps a balance can be struck so that imposing limits won’t encourage evildoers and compromise public safety. Still, having worked in policing, we’re skeptical that rules alone will keep cops from responding emotionally, and particularly in highly charged, violence-laden environments such as Memphis. What’s needed? We could start by frankly discussing such things in the academy and at all levels of police organizations. How can the craft of policing – it is an art form, by the way – be practiced so that it resists the unholy influences of the workplace? And we mean the whole environment: both citizens and cops.

Give it a whirl. And if you do, let us know how it pans out!

UPDATES (scroll)

5/8/25 A prosecution expert testified that the repeated blows to the arrestee’s head were unnecessary. And an ex-cop testified that he regretted not stopping the assault. But a State jury nonetheless acquitted ex-Memphis cops Tadarrius Bean, Justin Smith and Demetrius Haley of all charges over their alleged 2023 beating death of Tyre Nichols, who had fled from their colleagues after forcefully resisting a traffic stop. Still, each former member of the “Scorpion” anti-crime team was convicted on moderately severe Federal charges last year and will soon face sentences that could run as high as twenty years.

12/5/24 In January 2023 Memphis PD’s “Scorpion” unit savagely beat Tyre Nichols. And now, nearly two years later, DOJ issued a “blistering” 73-page report that accuses Memphis cops of routinely using excessive force and discriminating against Black persons and the disabled. Officers are faulted for misusing traffic stops, and are allegedly seldom held accountable for misconduct. But Memphis refuses to voluntarily enter into a consent decree and place its cops under DOJ supervision. So a legal battle looms. DOJ announcement

11/18/24 Ex-Memphis cops Tadarrius Bean, Justin Smith and Demetrius Haley were recently convicted on assorted Federal civil rights charges for the January 2023 beating death of Tyre Nichols. Their sentencing is scheduled for January 2025. And in April they will go on State trial for murder. Two other officers that were members of the “Scorpion” team, Emmitt Martin and Desmond Mills Jr., pled guilty to the Federal charges and testified against their colleagues. Their State cases are pending.

10/4/24 Jurors convicted the remaining three ex-Memphis cops who participated in the lethal beating of Tyre Nichols. But the verdicts were mixed. None was convicted of the most serious civil rights violation, causing a death, which carries a life sentence. Tadarrius Bean and Justin Smith were acquitted of civil rights charges altogether, while Demetrius Haley was convicted of a lesser civil rights violation that carries up to ten years imprisonment. All were convicted of witness tampering, which can bring up to a 20-year sentence. Haley was also convicted of conspiracy to witness tamper. DOJ news

release

9/13/24 Two ex-Memphis cops have pled guilty to beating Tyre Nichols during their ill-fated January 2023 encounter. At the ongoing Federal civil rights trial of the remaining three - Tadarrius Bean, Demetrius Haley and Justin Smith - which began Monday, an MPD lieutenant testified that “if the goal is to get him in handcuffs” punching, kicking and striking Mr. Nichols with a baton violated agency policy. Instead, the officers should have used “armbars, wrist locks and other soft hands tactics.” And kept each other on the right track. (See 11/3/23 and 8/26/24 updates)

8/26/24 Following on the footsteps of former Memphis police officer Desmond Mills, who pled guilty to Federal charges last November, Emmitt Martin III has become the second ex-Memphis cop to plead guilty to violating the civil rights of Tyre Nichols. Extensive video evidence depicts Mills, Martin and three other officers savagely beating and crushing Mr. Nichols to death during a January 2023 encounter. Their three former colleagues, who have also been fired, remain on track for a September 9th. trial. (See 11/3/23 and 9/13/24 updates)

5/9/24 Ex-Memphis cop Patric J. Ferguson and a civilian are pending State trial for the 2021 on-duty kidnapping and murder of Robert Howard. His body was dumped in a river and his car was sold for scrap metal. Out on bail, they’re now back in custody facing Federal civil rights charges for the same acts. On April 12, 2024 Memphis officer Joseph McKinney was killed during a shootout with suspect Jaylen Lobley. Officer McKinney’s death is now being attributed to shots fired by fellow officers. Lobley had been released without bail one month earlier after being arrested in a stolen car in which he carried a firearm that had been illegally converted to fire fully automatically.

4/1/24 In the aftermath of Tyre Nichols’ brutal death, Memphis enacted a law that prohibits officers from using minor reasons, such as a broken taillight or expired license plate, to make traffic stops. Criticizing its effects on policing, Tennessee legislators introduced a bill that prohibits cities from enacting such measures. Despite concerted opposition from civil rights groups, it was just signed into law.The Federal trial of four ex-Memphis cops for violating Mr. Nichols’ civil rights is now set for September 2024. It will be followed by their State trial on murder charges.

1/11/24 Exemplified by the savage beating of Tyre Nichols by Memphis P.D.’s “Scorpion” team last January, a concern that (among many other things) “culture eats policy for lunch” led DOJ to publish “Considerations for Specialized Units: A Guide for State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies to Ensure Appropriateness, Effectiveness, and Accountability.” Two main aspects, “Setting the Culture” and “Community Engagement” emphasize the need to insure that agency and team cultures support policies and procedures and are responsive to citizen needs and expectations. Report

12/5/23 Reasoning that “violent crime deprives communities of a fundamental sense of security in their own homes and neighborhoods,” DOJ announced a major new effort to target gangs and violence in Memphis. Partnering with local police, ATF and the FBI will apply “data-driven, targeted, and focused enforcement” techniques to dismantle criminal networks through Federal and State prosecutions. Community members will also play a key role in identifying problems and devising solutions.

12/1/23 Ex-Shreveport, Louisiana police officer Dylan Hudson was sentenced to 21 months in Federal prison after a second jury found him guilty of Federal civil rights violations. Hudson was convicted of “punching, kneeing, Tasing, pistol-whipping and slamming the head” of Markeil Tyson, a trespassing suspect whom fellow officers detained in August 2019. They testified that Tyson was not resisting and that Hudson’s actions violated both training and policy. (See 7/5/23 update)

11/3/23 Ex-Memphis cop Desmond Mills, one of five officers involved in the brutal arrest of Tyre Nichols last January, pled guilty to Federal civil rights charges. Among other things, he admitted repeatedly striking Nichols with a baton, failing to stop his colleagues from using excessive force, and lying to superiors about what took place. Mills faces up to fifteen years imprisonment. His four colleagues are on track for a May 6 trial. (See 8/26/24 and 9/13/24 updates)

10/23/23 Federal-local task forces used information from crime gun recoveries to target firearms and drug distribution networks in violence-beset Memphis and New Orleans. During both summer-long operations, many stolen firearms, guns with illegal “machinegun conversion” switches and weapons without serial numbers were seized. In Memphis, twenty-one defendants face Federal charges of illegal gun possession, unlicensed gun dealing, and drug trafficking. In New Orleans, forty-one have been charged with similar offenses in Federal and State Courts.

9/25/23 Baton Rouge police are accused of taking freshly detained or arrested persons to a warehouse operated by the Street Crimes unit. Nicknamed the Brave Cave or “torture warehouse”, it’s a place where cops allegedly conducted rough interrogations and subjected persons to brutal treatment, including kicking and punching, away from public view. So far it’s generated two Federal lawsuits. One of the defendants, an officer who has resigned, faces charges of misusing a stun gun in a separate incident.

9/1/23 Memphis PD’s reputation took another hit as former officer Armando Bustamante was sentenced to 18 months in Federal prison for civil rights violations. According to DOJ, Bustamante admitted that he needlessly used force and injured an arrested person by striking him in the head with his hands and gun during a January 2021 encounter.

7/28/23 Seven months after the beating death of Tyre Nichols by a squad of anti-crime officers, the Department of Justice announced that it will conduct a pattern-or-practice inquiry into the Memphis Police Department. It’s supposedly not just about Nichols. According to information reviewed by DOJ, Memphis police exhibit “a dangerously aggressive approach to traffic enforcement” and its officers disproportionately stop Black drivers “for minor violations.” (See 3/9/23 update)

7/5/23 Federal jurors convicted a White Shreveport, Louisiana police officer of civil rights violations for punching, kneeing, Tasing, pistol-whipping and slamming the head of an unarmed Black man into the ground. His victim, Markeil Tyson, had reportedly trespassed at a liquor store, and he was on the ground being detained by two other officers when former cop Dylan Hudson stepped in. Mr. Tyson died in a traffic accident before ex-cop Hudson’s first trial last December, and that jury had deadlocked. Video DOJ news release (See 12/1/23 update)

6/19/23 Spurred by the murder of George Floyd, DOJ’s “patterns or practices” investigation of Minneapolis PD paints a grim picture. According to Attorney General Merrick Garland, MPD officers frequently used excessive force, discriminated against Black and Native American persons, mistreated persons suffering from behavioral disorders, and violated free-speech rights. MPD officers “routinely disregarded the safety of people in their custody” and failed to intervene when their colleagues were abusing citizens. Full DOJ Report Attorney General’s summary

6/1/23 Faced with officer shortages and difficulties in recruitment, police departments across the U.S. are loosening hiring standards. Some are offering hiring bonuses. Others, including Chicago and New Orleans, have dropped college requirements. Physical testing has become more forgiving (Massachusetts eliminated sit-ups). A few (Golden, Colorado) are experimenting with 4-day, 32-hour workweeks. But not everyone’s on board. Memphis officers fear that relaxed standards will bring on more unqualified candidates and lead to more episodes such as the beating death of Tyre Nichols.

5/16/23 Former Indianapolis Police Sgt. Eric Huxley pled guilty to Federal civil rights violations over a Sept. 2021 incident in which he stomped a disorderly and combative man in the face even though other officers had taken him to the ground and had him under complete control. Huxley’s actions, which were caught on video, have also led to state charges and a lawsuit. DOJ news release

5/5/23 According to the coroner’s report, Tyre Nichols, who was severely beaten by Memphis police officers during a January 7 traffic stop, died from “blunt force injuries to the head.” The five officers who encountered him at the streetcorner were fired and charged with second-degree murder. Each pled not guilty on February 17.

3/13/23 Beset by a shortage of applicants, Memphis P.D. dropped college-credit requirements in 2018 and began hiring candidates with a high-school diploma and work experience. Academy standards were lowered and grading was made far more lenient. Officers say that these and other easings in hiring and retention standards led to hiring the five officers who now face prosecution in the killing of Tyre Nichols.

3/9/23 At the request of Memphis officials, DOJ will conduct a review of its police department’s policies, practices, and training in regards to use of force and de-escalation. DOJ will also address the management of specialized units, such as the “Scorpion” team that killed Tyre Nichols. That incident has also led DOJ to embark on a program that will “produce a guide” for cities across the U.S. about the purposes, training and management of specialized teams. (See 7/28/23 update)

Prompted by the 2020 killing of Breonna Taylor, DOJ’s civil rights inquiry into Louisville PD concludes that its officers engaged in a “pattern or practice” of First and Fourth Amendment violations, using excessive force, serving “invalid” warrants, and failing to properly announce their presence. Heavy criticism is levied on the deployment of aggressive “Viper” teams that made pretextual, often illegal stops in Black neighborhoods. Negotiations for a consent decree are reportedly in the works.

2/20/23 On February 18 Memphis police officer Geoffrey Redd succumbed to a gunshot wound sustained while on duty on February 2. On that day, Officer Redd and his partner responded to a call about a man who had trespassed on a local business, then entered a public library and threatened a patron. When the officers arrived at the library the suspect pulled a gun and opened fire, wounding officer Redd. His partner’s return fire killed the assailant. And during the early morning hours of February 19 gunfire broke out in the area of a Memphis nightclub, leaving one person dead and eleven wounded, five critically. Videos depict likely suspects but no arrests have yet been announced.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES

The Craft of Policing

RELATED POSTS

Special topics: Craft of Policing Neighborhoods Stop-and-Frisk and Hot Spots

Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job (III) Good News/Bad News Piling On What’s Up? Violence. Where?

Massacres, in Slow-Mo Woke Up, America! Full Stop Ahead Recipe for Disaster

Turning Cops Into Liars Select – Don’t “Elect” Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job (I)

Fix Those Neighborhoods! Violent and Vulnerable “SWAT” is a Verb

Did the Times Scapegoat L.A.’s Finest? (I) (II) Driven to Fail Two Sides of the Same Coin

Three (In?)explicable Shootings Too Much of a Good Thing?

Posted 2/3/23

DOES RACE DRIVE POLICING?

Renewed concerns that police target Black persons roil Los Angeles

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. In 2015 California legislators enacted Penal Code section 12525, the “Racial and Identity Profiling Advisory Act” (RIPA). Since 2018 all State and most local law enforcement agencies have been required to disclose public complaints of racial and identity profiling and furnish annual reports about pedestrian and vehicle stops (small agencies had until this year to comply.) Required information includes the reason for a stop, the race and ethnicity of pedestrians, drivers and other persons who influenced a stop decision, any use of force, and whether someone was detained or arrested, and why (for the official guide, click here.)

A Board was formed to oversee the process. Alas, its weighty, just-released 2023 Annual Report doesn’t offer much hope:

Over the past four years, the data collected under the Racial and Identity Profiling Act (“RIPA”) has provided empirical evidence showing disparities in policing throughout California. This year’s data demonstrates the same trends in disparities for all aspects of law enforcement stops, from the reason for stop to actions taken during stop to results of stop.

From their initial release, RIPA’s annual reports have blasted the seemingly unequal treatment of racial and ethnic minorities. Little has apparently improved:

Click here for the complete collection of conduct and ethics essays

Overall, the disparity between the proportion of stops and the proportion of residential population was greatest for Multiracial and Black individuals. Multiracial individuals were stopped 87.4 percent less frequently than expected, while Black individuals were stopped 144.2 percent more frequently than expected.

According to the report, Black persons comprised six percent of the State’s 2021 population but accounted for twenty-one percent of stops. Hispanics also shouldered a burden, although of substantially lesser magnitude (36 pct. of pop. v. 42 pct. of stops). On the other hand, White persons carried an advantage (35 pct. of pop. v. 31 percent of stops). Force, including lethal force, was also far more likely to be used against Black persons and substantially more likely to be used against Hispanic persons than against Whites.

On first read, RIPA’s 222-page piece seems a thorough work. But as our readers know, we’re concerned about the influence of economic conditions on crime. As to these, RIPA’s silent. While its report insists that it did “closely analyze and isolate calls for service, stops, and other contacts to identify disparities while controlling for factors like neighborhood crime and poverty levels” (p. 216), RIPA kept mum about crime rates or economic conditions. So their impact (if any) on agency and officer decisions was ignored.

From the start, critics have used RIPA data to accuse California cops of discriminating against members of minority groups. Our 2019 two-parter (“Did the Times Scapegoat L.A.’s Finest?”) was prompted by a series of articles in the Los Angeles Times that used RIPA data to question why only 17.9 percent of LAPD’s vehicle stops were of Whites. We selected a sample of one-hundred stops and took it from there. Our present journey was inspired by a recent piece in the Associated Press about RIPA’s reveal of similar racial and ethnic disparities in 2021 stops:

In more than 42% of the 3.1 million stops by those agencies in 2021, the individual was perceived to be Hispanic or Latino, according to the report. More than 30% were perceived to be white and 15% were believed to be Black. Statewide, however, 2021 Census estimates say Black or African American people made up only 6.5% of California’s population, while white people were about 35%. Hispanic or Latino people made up roughly 40% of the state’s population that year.

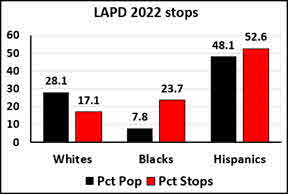

Well, 2022 RIPA stop data is in. We again focused on LAPD. (Click here for data on when and where stops took place, and here for details about suspects, officer actions, and outcomes.) Once again, the numbers create concern. According to Census ACS 2021 estimates, L.A.’s population is 28.1 percent White, 7.8 percent Black and 48.1 percent Hispanic. Yet only 17.1 percent of the 330,075 stops in 2022 were of White persons. Black persons were stopped at a rate about three times their share of the population, while Hispanics suffered a lesser disadvantage. Well, 2022 RIPA stop data is in. We again focused on LAPD. (Click here for data on when and where stops took place, and here for details about suspects, officer actions, and outcomes.) Once again, the numbers create concern. According to Census ACS 2021 estimates, L.A.’s population is 28.1 percent White, 7.8 percent Black and 48.1 percent Hispanic. Yet only 17.1 percent of the 330,075 stops in 2022 were of White persons. Black persons were stopped at a rate about three times their share of the population, while Hispanics suffered a lesser disadvantage.

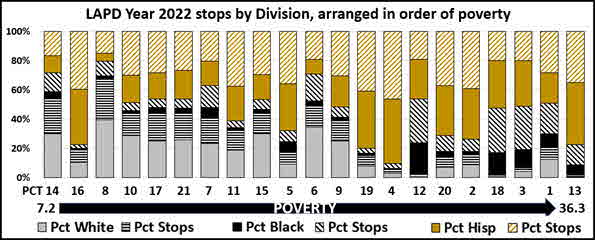

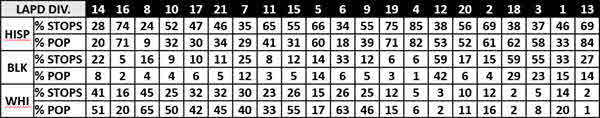

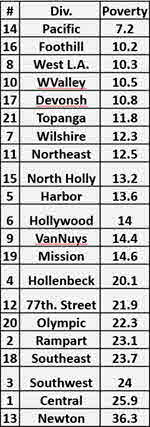

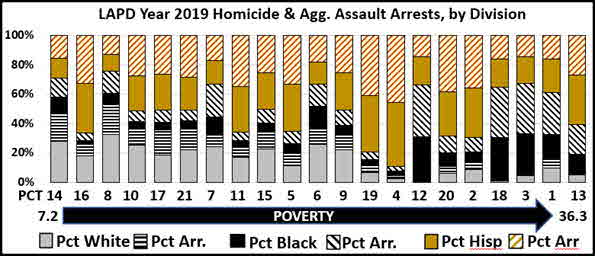

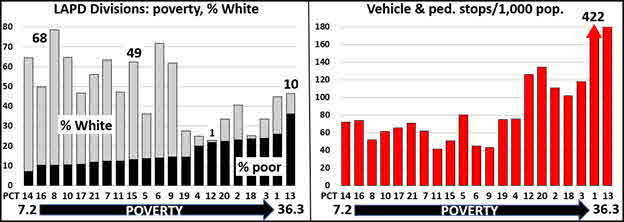

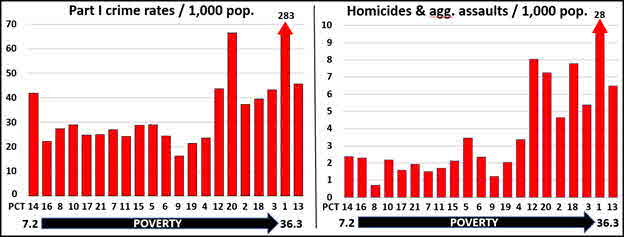

What’s more, Black persons were stopped at higher rates throughout Los Angeles. This graphic, which we generated using RIPA data, arranges police Divisions by poverty, from prosperous Division 14, “Pacific”, where only 7.2 percent of residents are poor, to the impoverished Division 13, “Newton”, where 36.3 percent are poor:

(Division pop. figures are posted on each Division’s homepage. Racial and ethnic distributions are from the LAPD I.G.’s 2019 report. Division poverty was estimated by overlaying city ZIP codes onto the LAPD Division map and averaging Census poverty scores across ZIP’s. Division Part I crime rates, mentioned below, are from the L.A. City hub.) estimated by overlaying city ZIP codes onto the LAPD Division map and averaging Census poverty scores across ZIP’s. Division Part I crime rates, mentioned below, are from the L.A. City hub.)

RIPA mentions that Black persons were often stopped outside their area of likely residence. For example, White persons comprise 51 percent of the residents of prosperous Pacific Division but figured in only 41 percent of stops. Meanwhile Black persons, who only form eight percent of that Division’s population, accounted for twenty-two percent of stops. Indeed, White persons seemed to enjoy a modest advantage throughout. As poverty scores increase, their proportion of the population, and of stops, plunges. (One exception, Div. 1, “Central”, which covers L.A.’s downtown, has a small resident population but experiences a large influx during the daytime.)

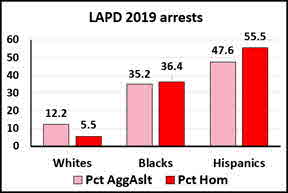

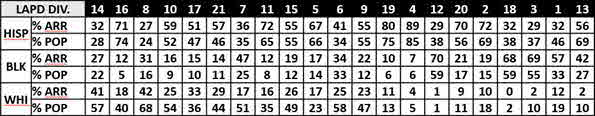

RIPA doesn’t collect data about crimes or arrests. For that we turned to the city’s public safety portal. On the left is a graphic that depicts the racial and ethnic distribution of LAPD arrests for aggravated assault and homicide in 2019 (the most recent year available), when 1,447 persons were arrested for homicide and 16,839 for aggravated assault. The disparities are obvious. RIPA doesn’t collect data about crimes or arrests. For that we turned to the city’s public safety portal. On the left is a graphic that depicts the racial and ethnic distribution of LAPD arrests for aggravated assault and homicide in 2019 (the most recent year available), when 1,447 persons were arrested for homicide and 16,839 for aggravated assault. The disparities are obvious.

Our next graphic arranges things as we did for stops:

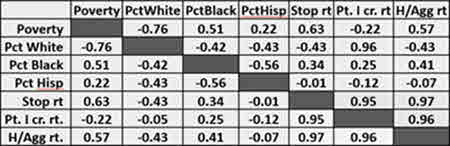

Black persons seem substantially over-represented as alleged perpetrators of violent crimes, and particularly in the poorer districts. But there’s lots of numbers. So we turned to the “r” (correlation) statistic. (It ranges from zero to one. Zero means no relationship between variables; one reflects a perfect lock-step association. Positive r’s mean that variables move up and down together; a negative [-] r indicates that they travel in opposite directions.)

Consider the relationship between Pct. White and Poverty. That strong negative r (-.76) means that as the proportion of White residents in a Division increases, percent poor consistently declines. In contrast, Pct. Black’s r with Poverty, a relatively strong [+] .51, indicates that Black residents and poverty increase and decrease pretty much in unison. There’s a similar relationship, but of lesser strength, between Pct. Hispanic and Poverty. And note that strong “positive” relationship between Poverty and Stop rates. Its r, a robust [+] .63, would yield highly visible, real-world consequences at poverty’s higher levels, say, from Div. 12 (“77th. Street”) on.

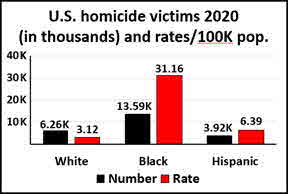

As one might expect, Part I crimes and Homicide/Agg. Assault rates are in near-perfect sync. Ditto, the relationship of each with stop rates. Maybe LAPD’s focus really was on high-crime areas. But put stops aside. What’s most troubling is that as the proportion of Black residents increases, a Division’s inhabitants become considerably more likely to fall victim to violent crime. Indeed, the (+) .41 between Pct. Black and H/Agg. is a virtual opposite to the -.43 between Pct. White and H/Agg. That’s common throughout the U.S. Grab a look at the right graphic, which displays CDC’s 2020 national homicide victimization rates. As one might expect, Part I crimes and Homicide/Agg. Assault rates are in near-perfect sync. Ditto, the relationship of each with stop rates. Maybe LAPD’s focus really was on high-crime areas. But put stops aside. What’s most troubling is that as the proportion of Black residents increases, a Division’s inhabitants become considerably more likely to fall victim to violent crime. Indeed, the (+) .41 between Pct. Black and H/Agg. is a virtual opposite to the -.43 between Pct. White and H/Agg. That’s common throughout the U.S. Grab a look at the right graphic, which displays CDC’s 2020 national homicide victimization rates.

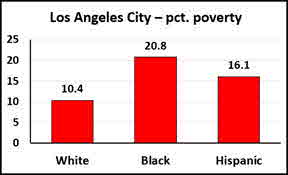

Police Issues has always rejected the notion that race and ethnicity “cause” crime and violence. Instead, we’ve consistently laid the blame on poor economic conditions. And even in supposedly prosperous Los Angeles, material wealth is sharply distributed according to skin color. Just consider the challenges of living in an economically-challenged neighborhood: poor education, lousy child care, a lack of marketable skills, substandard housing, and an absence of health care and other critical supports. (For a “primer” check out “Fix Those Neighborhoods”. It’s part of our “Neighborhoods” special section, which offers a wealth of posts on point.) Police Issues has always rejected the notion that race and ethnicity “cause” crime and violence. Instead, we’ve consistently laid the blame on poor economic conditions. And even in supposedly prosperous Los Angeles, material wealth is sharply distributed according to skin color. Just consider the challenges of living in an economically-challenged neighborhood: poor education, lousy child care, a lack of marketable skills, substandard housing, and an absence of health care and other critical supports. (For a “primer” check out “Fix Those Neighborhoods”. It’s part of our “Neighborhoods” special section, which offers a wealth of posts on point.)

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Let’s bring it together. Set aside ideologically-infused narratives. Or even our well-intentioned try at objectivity. Share these two graphics with your friends. They really do say it all:

p.s. As we were putting the finishing touches on this piece, Memphis happened. An indisputable abuse by some clearly out-of-control cops, and a man died. We’ve got an approach that might prove of value. Stay tuned!

UPDATES (scroll)

2/13/23 Do LAPD and Sheriff’s helicopters purposely fly lower over Black communities? That’s the claim in a lawsuit filed against L.A. County by the “Stop LAPD Spying Coalition” and UCLA’s “Carceral Ecologies Lab,” which researches the “prison industrial complex.” According to its director, an assistant professor, “the higher the proportion of Black population, the lower the altitude of the helicopter.” Their noise, according to the complainants, creates a “threatening atmosphere” and interferes with sleep.

2/10/23 Prospects seem excellent that many past criminal cases referred by members of Memphis PD’s “Scorpion” unit, which was disbanded after the killing of Tyre Nichols, will be dismissed. Shelby County’s D.A. has promised to review prosecutions that hinged on the testimony of officers now thought to be dishonest or facing prosecution. Hundreds of cases in which they participated are at risk, and defense lawyers are busily gearing up.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES

Memo to Joe Biden: Focus on Neighborhood Safety (The Crime Report, Dec. 7, 2020)

RELATED POSTS

Neighborhoods special topic

Is Crime Really Down? It Depends... Good News/Bad News

Did the Times Scapegoat L.A.’s Finest? (I) (II) Fix Those Neighborhoods! Black on Black

White on Black Good Guy/Bad Guy/Black Guy (I) (II)

|